A DIFFERENT APPROACH TO DIFFICULTY

A paradigm shift away from the idea that games should find more and more complex ways to serve players with different skill levels. But rather, they should give players with the tools to cook to their own palate, provided it is a meaningful experience.

EvilEagles

EvilEagles- 10/24/2018 06:49 AM

- 18798 views

The problem of difficulty in games has been debated to great depths for a long time. Various alternatives to the traditional approach with different difficulty modes at the beginning of a particular game have been proposed, analyzed and implemented. And yet, as much as they patch up the errors of the traditional approach, within them arise numerous inherent problems and difficulties. As such, I would like to propose another alternative–not so much a mechanical solution that requires implementation, but rather a different approach to difficulty design.

One thing I’d like to stress is that, this has been applied in various games quite successfully before, and I’ll mention them later on, but not to the extent to which it can deservedly become a central design philosophy, in my opinion. This I presume is due to a lack of a rather clear and deliberate approach to difficulty design.

But first, let me attempt to briefly summarize a few popular criticisms of the traditional difficulty modes approach and its alternative.

Problems with Difficulty Modes

Picture yourself coming into a brand new game, only to be asked to choose a difficulty mode that’s suitable for yourself, and presented with a number of different menu options. And frankly, they don’t do that good of a job at giving you sufficient information to make such an important decision. This is how many games in our history have done difficulty, and it continues to be fairly prevalent among modern games.

Here are its common criticisms:

There have been several solutions to negate these issues, of which Mark Brown has gone into depths in one of his videos. However, not one of them was able to solve them all and still maintain immersion.

Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment

The idea of Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment (or DDA) hinges on the theory of the player’s Flow State, in which the player is completely immersed, and the game’s difficulty feels just right. Any more difficulty will cause frustration and break immersion. Any less difficulty and the player will quickly find boredom, and you guessed it, lose immersion. Therefore, as designer Andrew Glassner put it in his book Interactive Storytelling, games “should not ask players to select a difficulty level. Games should adapt themselves during gameplay to offer the player a consistent degree of challenge based on his changing abilities at different tasks.” Or in other words, games should be implemented with a performance evaluation system as well as a dynamic difficulty adjustment system in order to adjust itself to accommodate the infinitely different and ever-changing characteristics of players. More on the technical details of DDA can be found in Robin Hunicke’s 2005 paper The Case for Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment in Games.

However, while the Flow State theory admittedly has its merits, the DDA approach doesn’t go without its numerous downsides:

There are many interesting and nuanced approaches to DDA that I won’t mention since that’s beyond the scope of this segment. While I imagine there are going to be a lot of way to make DDA functional and sufficiently inscrutable through clever algorithms and implementation, I am rather discussing the fundamentals.

Organic Difficulty in Games

There seems to be a number of different terms to address this approach, but just for this article I’m going to use the term “Organic Difficulty.” This is something that has been tossed around in the last decade or so.

The basic idea of Organic Difficulty is that the game does not ask the players to select or adjust their preferred difficulty via GUI-based commands, nor does it automatically adapt itself to match with the player’s performance and progress. But rather, the game allows the player to interact with it in certain ways to make it easier, or harder, for themselves. These take the form of tools, approaches, strategies, input sequences or methods, etc. which should often come with some sort of trade-off.

This is something that has been implemented in a number of games including From Software’s Dark Souls, which Extra Credits has dedicated an entire episode to, and which everyone should take a look.

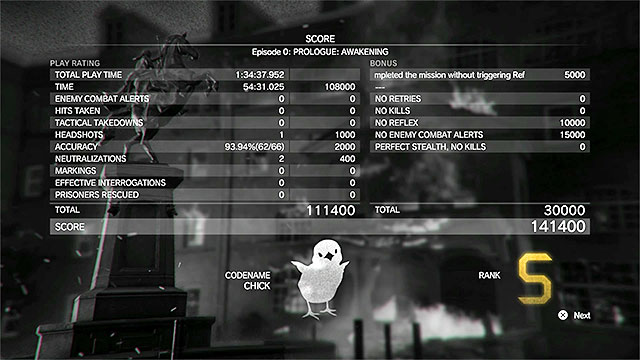

In Metal Gear Solid V, for every mission the player has completed, there’s a score rating system which provides a rough overview of the player’s performance based on a number of factors such as stealth, lethality, accuracy, completion speed, whether the player has completed any mission tasks, and what tools they used. While the player does get minus points for mistakes such as getting detected, raising enemy alert, taking hits, etc. some other factors are not as clear-cut as to how they constitute minus points aside from narrative reasons. The player can always go on a lethal rampage, tossing grenades at everybody in sight, or calling a support helicopter to airstrike the entire enemy base. The player is provided the tools to do exactly all of those, and they’re always just a few buttons away, and the worst they get is a C rank, provided they completed the mission, and a slight dip in their earnings.

Another example of this can be found XCOM: Enemy Within. There's a "cheesy" tactic in the game that can almost ensure victory, which is to have a unit with the Mimetic Skin ability to safely spot the enemies, thus enabling a squadsight-sniper from across the entire map to pick them off one-by-one safely without any real repercussion. This strategy is extremely effective in virtually every mechanical aspect of combat, with the only risk being that the spotter must not be flanked for they would instantly lose invisibility. The actual problem with this strategy is that it’s incredibly boring: your snipers just simply shoot every turn, and you can only take a few shots every turn, not to mention reloading. This strategy is best suited for beginners and people who have made mistakes and want to get out of the downward spiral. While on the other end of the spectrum, there are players who understand how the game and the AI of every alien unit in the game work, so they are more confident about moving up close and personal with enemies with minimal armor. Because for them, it's not about defending against the enemies, but about manipulating, "nudging" the enemies into behaving the way these players want them to (e.g. nobody needs armor when enemies are only going to attack the tank; nobody needs to take good cover when enemies are too scared to move to flank in front of an Opportunist-overwatch unit; etc.)

The above examples seem to imply a few important points regarding difficulty:

The Effectiveness-Ludoaesthetics Spectrum (ELS)

On the Effectiveness-Ludoaesthetics Spectrum (ELS), difficulty exists only at the lowest technical level. Each end of the ELS represents what each player wants at a certain point in the game with certain conditions. On this spectrum, games are designed with the player’s interactions, approaches and strategies in mind, each with its own degree of effectiveness and ludoaesthetics. These are not solely defined by mechanics or the player’s skill level, but rather the way in which they are experienced and perceived by the player.

Effectiveness refers to how well the player can progress and achieve their goals in a game using the set of tools they’re given and the strategies they’re allowed to formulate. How easy those tools are to use, and how good they are at helping the player progress towards the game’s intended goals, primarily constitute Effectiveness. Players who aim towards and stay on this end primarily look for the most effective ways to achieve the intended goals of the game (which of course include playing the game the easy way).

Ludoaesthetics refers to the perceivable aesthetic appeals of the aforementioned set of tools and strategies given to the players. Players who aim towards this end do not necessarily look for the most effective ways to achieve the intended goals. But rather they tend to look for the added intrinsic benefits derived from unconventional play. These benefits include:

Design for Ludoaesthetics

The point of designing for ludoaesthetics is NOT to create increasingly harder challenges in order to accommodate the player’s increasing skills (though that is not to say such approach has no merits whatsoever). But rather, it is actually to encourage players to strive for aesthetics in their gameplay and to lean more towards the right side of the spectrum.

Here are a few suggestions on how to go about it.

Creating more depth

Depth refers to the amount of space the player is allowed to make interesting choices using the set of tools they’re given by a game. For a more detailed explanation of what Depth is in comparison to Complexity, you can take a look at Extra Credits’ episode on Depth vs. Complexity.

Essentially, Complexity is the amount of constituent elements that make up a game, and Depth is the degree of interactivity between those elements. The very nature of ludoaesthetics has to do with the deviation from the default, intended approach (a.k.a. Playing “by-the-book.”) Therefore, the more those elements “talk” to one another, the better chance it is for ludoaesthetics to emerge, because then the player will be able to find more different ways to control or manipulate each element.

[Also read: Design for Theorycrafting]

Depth is pretty much the prerequisite for ludoaesthetics even as a concept to exist. Without a lot of depth, the window of opportunities for ludoaesthetics get significantly lower or completely non-existent.

Creating patterns suggesting the possibility of gameplay aesthetics

Adding more depth is not only about simply adding more stuff in a game and making them as obscure as they possibly can be. It is also about leaving breadcrumbs to suggest that there is more than meets the eye, therefore encouraging players to explore further possibilities. What kind of depth to even add? And how does one go about communicating it?

Below is a conceptual representation of a set of challenges typically found in video games.

Each challenge is represented by a window of failure and a window of success. These windows can be spatial, temporal, symbolic, strategic, or a combination of all. They are the spaces in which the player enters by behaving in a certain expected way. Secondly, the black line represents the player’s interactive maneuvers: where to get across and which direction to turn to next, in order to overcome the set of challenges without stumbling into the windows of failure.

For example, say we have a situation in a 3D platformer game where the player is facing a pit, and across the pit leaning towards the right side there is a narrow platform. In such a scenario, we can assume that the window of failure includes any and all sets of behaviors that lead the player plummeting down the pit, and the window of success includes those that lead the player to landing on the platform across the pit safely.

Now consider the same representation of challenge above, but this time with a slight deliberate arrangement.

As you can see, the sizes of the windows of failure and the windows of success stay exactly the same, but the positions of the windows of success have been altered so that they align somewhat (but not exactly aligned to the point of being too obvious). You can see that nested within the windows of success is a narrower window where the amount of the player’s maneuvers stays extremely minimal. Stepping into this window offers the opportunity for a non-disrupted gameplay flow, where a deliberate and guided set of behaviors will let the player “breeze” through the challenges seemingly almost with ease. This window is where ludoaesthetics occur.

Of course, the downsides of it are aplenty: it can be extremely difficult to realize such a window exists in a real scenario. And in order to stay inside such a narrow window, the player has to be extremely precise and/or smart in their gameplay. You can think of this window of non-disrupted flow as an intended “weak point” of the challenge, where a single and concentrated attack will break the whole thing apart in one fell swoop. But the process of identifying such a weak point, and delivering the finishing blow with great accuracy may require a lot of trials and errors, and can be extremely tedious and/or difficult.

An Example from Master Spy

A common manifestation of ludoaesthetics comes in the form of speedrunning. Finishing with speed is, for the majority of games, not the primary intended goal. Games are rarely ever designed to be speedrun, and most players do not have to finish any games at high speed in order to not miss anything. So speedrunning has always been a sort of arbitrary self-imposed challenge by those who seek greater sense of enjoyment from their favorite games.

However, there are a few exceptions. And you can find the above mentioned window of non-disrupted flow in levels like this one from Master Spy by Kris Truitt.

In this game you play the role of the Master Spy, to infiltrate ridiculously well-guarded buildings, palaces and fortresses with a huge number of different enemies, hazards and contraptions standing in your way. And you are given no tools whatsoever but an invisibility cloak that can help you sneak past the eyesight of certain enemies while halving your movement speed.

In the example above, your goal is to retrieve the keycard on the other side of the wall slightly to the right of your starting point, and then to escape through the white door right above your starting point safely. And while your cloak can get you past the eyesight of the guards, it is of no use whatsoever against the dogs, who can smell you even when you’re cloaked and will sprint forwards to attack you at horrendous speed as soon as you’re on the same ground as them.

So what you have to do as a sequence of actions in this level is first to cloak yourself, then drop down from the first ledge past the the first guard, then quickly decloak to regain speed as the cloak is useless against the incoming dogs. Then before the first dog reaches you, move forward to the right, then quickly jump up. Keep jumping to retrieve the keycard while avoiding the second and third dog. Cloak up, then get on the ledge with the three moving guards. Finally, jump to the left to reach your destination.

However, as you can see from the footage above (courtesy of a speedrunner nicknamed Obidobi), as soon as the player reaches the ledge with the three moving guards on the right, the guards turn to the other side and begin moving away from where the player is, effectively freeing the player from having to cloak and having their movement speed halved. And then right before the player reaches for the white door, the guard on the far right is about to touch the wall and thereby turning back to the left. This is such a tiny window of success that should the player not have begun moving right after they start the level and stayed uncloaked at the end, they would have failed. The level is designed in such a way that it can be completely solved without wasting any moment and action.

Is it significantly more difficult to play this way? Yes. Was this arrangement absolutely necessary? Not really. But the designer made the level with the expectation that people are going to speedrun the game and will be looking to optimize their timing with each level. Thus, the levels in Master Spy are designed so that should the player start looking to speedrun the game, they will easily recognize that sweet, sweet window of non-disrupted flow. It is an immensely satisfying experience to discover it.

Ensure Usability

As usual, it is easy to get too extremely logical about design and forget all about the equilibrium, which is almost always what design is about.

In this case, it is important that designers must ensure that whatever tools they’re making for their players to achieve ludoaesthetics, MUST have at least some sort of usability, even if it’s incredibly niche or extremely difficult to pull off. Things that serve nothing and mean nothing are NOT aesthetic. Say you have an RPG, and one of your players goes out of their way in order to build an unconventional character because they see some sort of future potential from this build, only to find out later that when they’re finished with the build, the meta of the game has changed and the window of opportunity for such a build has long passed. This means that the entire amount of depth you added, and the ludoaesthetics you might have intended by allowing that player to go in such a way, is utterly useless and entirely wasted. So always remember to ensure usability for everything you add in your game.

Conclusion

Organic Difficulty and the ELS are not only, and not necessarily, an alternative solution to the whole difficulty problem. But rather, they represent an entire paradigm shift away from the idea that games should find more and more complex ways to serve players with different skill levels, and towards a design philosophy where players are given integrated tools within the context of games to set their own difficulty at any point without breaking immersion and perhaps the extra baggage of shame. It is not enough to have your players stay at the same level of difficulty throughout the game, or dynamically adjust the difficulty on the fly to suit them. It is best, in my opinion, to let your players cook to their palate. Just make sure that the process of cooking and the game itself are one and the same.

References

One thing I’d like to stress is that, this has been applied in various games quite successfully before, and I’ll mention them later on, but not to the extent to which it can deservedly become a central design philosophy, in my opinion. This I presume is due to a lack of a rather clear and deliberate approach to difficulty design.

But first, let me attempt to briefly summarize a few popular criticisms of the traditional difficulty modes approach and its alternative.

Problems with Difficulty Modes

Picture yourself coming into a brand new game, only to be asked to choose a difficulty mode that’s suitable for yourself, and presented with a number of different menu options. And frankly, they don’t do that good of a job at giving you sufficient information to make such an important decision. This is how many games in our history have done difficulty, and it continues to be fairly prevalent among modern games.

Here are its common criticisms:

- Asking the player to make such a decision right at the beginning is not exactly a good idea. To select a difficulty mode before the game even starts is to make a major commitment based on very little information available (e.g. a short description). Once the player has selected a difficulty, they are probably going to live with it for the entire playthrough.

- Even if the game allows the player to change the difficulty mode later on, it is, in itself, still not a very good idea. For one, explicitly selecting a difficulty mode in a menu-based manner is certainly not an interesting choice that games strive to offer their players. They do not have to weigh anything against anything. They do not have to analyze the risks and rewards coming as a result of each option. And generally speaking, players are not going to be good at weighting short-term convenience against long-term enjoyment. They just do not know the game enough.

- Such approach would defeat the entire point of progression through unlocking higher and better tools to enhance and assist with gameplay. It would go against the intended gameplay experience from the game designer. And most importantly, it would make the player feel judged for not choosing a higher difficulty.

There have been several solutions to negate these issues, of which Mark Brown has gone into depths in one of his videos. However, not one of them was able to solve them all and still maintain immersion.

Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment

The idea of Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment (or DDA) hinges on the theory of the player’s Flow State, in which the player is completely immersed, and the game’s difficulty feels just right. Any more difficulty will cause frustration and break immersion. Any less difficulty and the player will quickly find boredom, and you guessed it, lose immersion. Therefore, as designer Andrew Glassner put it in his book Interactive Storytelling, games “should not ask players to select a difficulty level. Games should adapt themselves during gameplay to offer the player a consistent degree of challenge based on his changing abilities at different tasks.” Or in other words, games should be implemented with a performance evaluation system as well as a dynamic difficulty adjustment system in order to adjust itself to accommodate the infinitely different and ever-changing characteristics of players. More on the technical details of DDA can be found in Robin Hunicke’s 2005 paper The Case for Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment in Games.

However, while the Flow State theory admittedly has its merits, the DDA approach doesn’t go without its numerous downsides:

- Some players, when they find out about DDA, hate it. Especially when DDA cannot be turned off, the player ends up feeling patronized, and not respected by the game as an adult, capable of taking on challenges and improving him/herself.

- Players can, and will, learn to exploit DDA by pretending to be worse at playing than they actually are. And oftentimes, a DDA system will require some sort of break time in order to avoid revealing itself to the player, thus not able to quickly adapt itself to the player’s ostensible skill level.

- DDA inhibits the player’s ability to learn and improve. As soon as the player improves, the difficulty ramps up to match their skill level, thus eliminating the possibility of positive results. If the player cannot see some sort of feedback from the game regarding their performance, they cannot know whether any changes in their approach to gameplay were effective.

- DDA may create absurdities. One of the popular example of DDA going awry is the rubber-band effect in racing games, where opponents speed up and slow down seemingly for no reason in order to adapt to the player’s performance.

- DDA is incompatible with some forms of challenge. If the challenge in question is numerically-based, then DDA can work easily. However, when the challenge is symbolical, with pre-designed elements that are nakedly visible to the player, often having only one or a few intended solutions, then DDA cannot work.

There are many interesting and nuanced approaches to DDA that I won’t mention since that’s beyond the scope of this segment. While I imagine there are going to be a lot of way to make DDA functional and sufficiently inscrutable through clever algorithms and implementation, I am rather discussing the fundamentals.

Organic Difficulty in Games

There seems to be a number of different terms to address this approach, but just for this article I’m going to use the term “Organic Difficulty.” This is something that has been tossed around in the last decade or so.

The basic idea of Organic Difficulty is that the game does not ask the players to select or adjust their preferred difficulty via GUI-based commands, nor does it automatically adapt itself to match with the player’s performance and progress. But rather, the game allows the player to interact with it in certain ways to make it easier, or harder, for themselves. These take the form of tools, approaches, strategies, input sequences or methods, etc. which should often come with some sort of trade-off.

This is something that has been implemented in a number of games including From Software’s Dark Souls, which Extra Credits has dedicated an entire episode to, and which everyone should take a look.

In Metal Gear Solid V, for every mission the player has completed, there’s a score rating system which provides a rough overview of the player’s performance based on a number of factors such as stealth, lethality, accuracy, completion speed, whether the player has completed any mission tasks, and what tools they used. While the player does get minus points for mistakes such as getting detected, raising enemy alert, taking hits, etc. some other factors are not as clear-cut as to how they constitute minus points aside from narrative reasons. The player can always go on a lethal rampage, tossing grenades at everybody in sight, or calling a support helicopter to airstrike the entire enemy base. The player is provided the tools to do exactly all of those, and they’re always just a few buttons away, and the worst they get is a C rank, provided they completed the mission, and a slight dip in their earnings.

Another example of this can be found XCOM: Enemy Within. There's a "cheesy" tactic in the game that can almost ensure victory, which is to have a unit with the Mimetic Skin ability to safely spot the enemies, thus enabling a squadsight-sniper from across the entire map to pick them off one-by-one safely without any real repercussion. This strategy is extremely effective in virtually every mechanical aspect of combat, with the only risk being that the spotter must not be flanked for they would instantly lose invisibility. The actual problem with this strategy is that it’s incredibly boring: your snipers just simply shoot every turn, and you can only take a few shots every turn, not to mention reloading. This strategy is best suited for beginners and people who have made mistakes and want to get out of the downward spiral. While on the other end of the spectrum, there are players who understand how the game and the AI of every alien unit in the game work, so they are more confident about moving up close and personal with enemies with minimal armor. Because for them, it's not about defending against the enemies, but about manipulating, "nudging" the enemies into behaving the way these players want them to (e.g. nobody needs armor when enemies are only going to attack the tank; nobody needs to take good cover when enemies are too scared to move to flank in front of an Opportunist-overwatch unit; etc.)

The above examples seem to imply a few important points regarding difficulty:

- Difficulty should not only be designed around the mechanics of a game. It should also take into account the aesthetics or elegance of those very mechanics.

- Punishment does not always have to be tangible or significant, as long as it is enough to indicate to players that they are straying off the intended experience. A good analogy would be physical pain. The pain itself is not what’s causing harm to your body. The physical wound is. Pain is merely a bodily signal to let you know that what’s happening right now is pretty bad and you probably shouldn’t let what just happened happen again. But remember, the choice is ultimately yours!

- It may not be a good idea to put people on the linear graph of "gaming skill" where some people are simply "softcore, not-so-good at video games" and some other are "hardcore and always challenge-seeking." The idea alone is absurd, because players on such a graph would move up and down constantly, even during a single playthrough. Some people pick things up faster than a game can predict with its tutorials' pacing. Some people due to real life reasons have to abandon the game for some time, and they lose a bit of their touch when they come back to it.

- Instead of judging the player’s skill and trying to accommodate every possibility, games should be judging player interactions instead, using a spectrum between Effectiveness and Aesthetics of Play (or what I shall humbly name Ludoaesthetics).

The Effectiveness-Ludoaesthetics Spectrum (ELS)

On the Effectiveness-Ludoaesthetics Spectrum (ELS), difficulty exists only at the lowest technical level. Each end of the ELS represents what each player wants at a certain point in the game with certain conditions. On this spectrum, games are designed with the player’s interactions, approaches and strategies in mind, each with its own degree of effectiveness and ludoaesthetics. These are not solely defined by mechanics or the player’s skill level, but rather the way in which they are experienced and perceived by the player.

Effectiveness refers to how well the player can progress and achieve their goals in a game using the set of tools they’re given and the strategies they’re allowed to formulate. How easy those tools are to use, and how good they are at helping the player progress towards the game’s intended goals, primarily constitute Effectiveness. Players who aim towards and stay on this end primarily look for the most effective ways to achieve the intended goals of the game (which of course include playing the game the easy way).

Ludoaesthetics refers to the perceivable aesthetic appeals of the aforementioned set of tools and strategies given to the players. Players who aim towards this end do not necessarily look for the most effective ways to achieve the intended goals. But rather they tend to look for the added intrinsic benefits derived from unconventional play. These benefits include:

- Superficial Attractiveness: Visual and auditory appeal of using the subject matter or the subject matter itself. It can be represented by any entity the player can recognize in the game such as a character with great visual design, a badass-looking weapon with satisfying visual and sound effects, etc.

- Competitiveness: a.k.a. bragging rights. This is rather self-explanatory. There is always that portion of players who keep seeking greater and greater challenges to prove themselves to the world. They may even go as far as handicapping themselves with arbitrary limitations to heighten the challenge.

- Greater sense of satisfaction derived from greater challenges that may go beyond the goals intended by the game. People who have been through heights of overwhelming odds know about, and may expect, the immense amount of satisfaction that comes with them.

- Narrative Fantasy: Players may look for things that may not be effective or productive in terms of gameplay because they would align with the narrative better (in games that understandably contain some degree of ludonarrative dissonance), or they would add an extra layer of depth and intensity to the narrative and thereby enhancing it. Essentially, they’re sacrificing gameplay optimality to elevate their narrative fantasy.

Design for Ludoaesthetics

The point of designing for ludoaesthetics is NOT to create increasingly harder challenges in order to accommodate the player’s increasing skills (though that is not to say such approach has no merits whatsoever). But rather, it is actually to encourage players to strive for aesthetics in their gameplay and to lean more towards the right side of the spectrum.

Here are a few suggestions on how to go about it.

Creating more depth

Depth refers to the amount of space the player is allowed to make interesting choices using the set of tools they’re given by a game. For a more detailed explanation of what Depth is in comparison to Complexity, you can take a look at Extra Credits’ episode on Depth vs. Complexity.

Essentially, Complexity is the amount of constituent elements that make up a game, and Depth is the degree of interactivity between those elements. The very nature of ludoaesthetics has to do with the deviation from the default, intended approach (a.k.a. Playing “by-the-book.”) Therefore, the more those elements “talk” to one another, the better chance it is for ludoaesthetics to emerge, because then the player will be able to find more different ways to control or manipulate each element.

[Also read: Design for Theorycrafting]

Depth is pretty much the prerequisite for ludoaesthetics even as a concept to exist. Without a lot of depth, the window of opportunities for ludoaesthetics get significantly lower or completely non-existent.

Creating patterns suggesting the possibility of gameplay aesthetics

Adding more depth is not only about simply adding more stuff in a game and making them as obscure as they possibly can be. It is also about leaving breadcrumbs to suggest that there is more than meets the eye, therefore encouraging players to explore further possibilities. What kind of depth to even add? And how does one go about communicating it?

Below is a conceptual representation of a set of challenges typically found in video games.

Each challenge is represented by a window of failure and a window of success. These windows can be spatial, temporal, symbolic, strategic, or a combination of all. They are the spaces in which the player enters by behaving in a certain expected way. Secondly, the black line represents the player’s interactive maneuvers: where to get across and which direction to turn to next, in order to overcome the set of challenges without stumbling into the windows of failure.

For example, say we have a situation in a 3D platformer game where the player is facing a pit, and across the pit leaning towards the right side there is a narrow platform. In such a scenario, we can assume that the window of failure includes any and all sets of behaviors that lead the player plummeting down the pit, and the window of success includes those that lead the player to landing on the platform across the pit safely.

Now consider the same representation of challenge above, but this time with a slight deliberate arrangement.

As you can see, the sizes of the windows of failure and the windows of success stay exactly the same, but the positions of the windows of success have been altered so that they align somewhat (but not exactly aligned to the point of being too obvious). You can see that nested within the windows of success is a narrower window where the amount of the player’s maneuvers stays extremely minimal. Stepping into this window offers the opportunity for a non-disrupted gameplay flow, where a deliberate and guided set of behaviors will let the player “breeze” through the challenges seemingly almost with ease. This window is where ludoaesthetics occur.

Of course, the downsides of it are aplenty: it can be extremely difficult to realize such a window exists in a real scenario. And in order to stay inside such a narrow window, the player has to be extremely precise and/or smart in their gameplay. You can think of this window of non-disrupted flow as an intended “weak point” of the challenge, where a single and concentrated attack will break the whole thing apart in one fell swoop. But the process of identifying such a weak point, and delivering the finishing blow with great accuracy may require a lot of trials and errors, and can be extremely tedious and/or difficult.

An Example from Master Spy

A common manifestation of ludoaesthetics comes in the form of speedrunning. Finishing with speed is, for the majority of games, not the primary intended goal. Games are rarely ever designed to be speedrun, and most players do not have to finish any games at high speed in order to not miss anything. So speedrunning has always been a sort of arbitrary self-imposed challenge by those who seek greater sense of enjoyment from their favorite games.

However, there are a few exceptions. And you can find the above mentioned window of non-disrupted flow in levels like this one from Master Spy by Kris Truitt.

In this game you play the role of the Master Spy, to infiltrate ridiculously well-guarded buildings, palaces and fortresses with a huge number of different enemies, hazards and contraptions standing in your way. And you are given no tools whatsoever but an invisibility cloak that can help you sneak past the eyesight of certain enemies while halving your movement speed.

In the example above, your goal is to retrieve the keycard on the other side of the wall slightly to the right of your starting point, and then to escape through the white door right above your starting point safely. And while your cloak can get you past the eyesight of the guards, it is of no use whatsoever against the dogs, who can smell you even when you’re cloaked and will sprint forwards to attack you at horrendous speed as soon as you’re on the same ground as them.

So what you have to do as a sequence of actions in this level is first to cloak yourself, then drop down from the first ledge past the the first guard, then quickly decloak to regain speed as the cloak is useless against the incoming dogs. Then before the first dog reaches you, move forward to the right, then quickly jump up. Keep jumping to retrieve the keycard while avoiding the second and third dog. Cloak up, then get on the ledge with the three moving guards. Finally, jump to the left to reach your destination.

However, as you can see from the footage above (courtesy of a speedrunner nicknamed Obidobi), as soon as the player reaches the ledge with the three moving guards on the right, the guards turn to the other side and begin moving away from where the player is, effectively freeing the player from having to cloak and having their movement speed halved. And then right before the player reaches for the white door, the guard on the far right is about to touch the wall and thereby turning back to the left. This is such a tiny window of success that should the player not have begun moving right after they start the level and stayed uncloaked at the end, they would have failed. The level is designed in such a way that it can be completely solved without wasting any moment and action.

Is it significantly more difficult to play this way? Yes. Was this arrangement absolutely necessary? Not really. But the designer made the level with the expectation that people are going to speedrun the game and will be looking to optimize their timing with each level. Thus, the levels in Master Spy are designed so that should the player start looking to speedrun the game, they will easily recognize that sweet, sweet window of non-disrupted flow. It is an immensely satisfying experience to discover it.

Ensure Usability

As usual, it is easy to get too extremely logical about design and forget all about the equilibrium, which is almost always what design is about.

In this case, it is important that designers must ensure that whatever tools they’re making for their players to achieve ludoaesthetics, MUST have at least some sort of usability, even if it’s incredibly niche or extremely difficult to pull off. Things that serve nothing and mean nothing are NOT aesthetic. Say you have an RPG, and one of your players goes out of their way in order to build an unconventional character because they see some sort of future potential from this build, only to find out later that when they’re finished with the build, the meta of the game has changed and the window of opportunity for such a build has long passed. This means that the entire amount of depth you added, and the ludoaesthetics you might have intended by allowing that player to go in such a way, is utterly useless and entirely wasted. So always remember to ensure usability for everything you add in your game.

Conclusion

Organic Difficulty and the ELS are not only, and not necessarily, an alternative solution to the whole difficulty problem. But rather, they represent an entire paradigm shift away from the idea that games should find more and more complex ways to serve players with different skill levels, and towards a design philosophy where players are given integrated tools within the context of games to set their own difficulty at any point without breaking immersion and perhaps the extra baggage of shame. It is not enough to have your players stay at the same level of difficulty throughout the game, or dynamically adjust the difficulty on the fly to suit them. It is best, in my opinion, to let your players cook to their palate. Just make sure that the process of cooking and the game itself are one and the same.

References

- The Designer's Notebook: Difficulty Modes and Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment (2008) by Earnest Adams. Retrieved at https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/132061/the_designers_notebook_.php

- The case for dynamic difficulty adjustment in games (2005) by Robin Hunicke

- Cognitive Flow: The Psychology of Great Game Design (2012) by Sean Baron. Retrieved at http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/166972/cognitive_flow_the_psychology_of_.php

- Depth vs. Complexity (2013) by Extra Credits. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jVL4st0blGU

- The True Genius of Dark Souls II (2014) by Extra Credits. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MM2dDF4B9a4

- What Makes Celeste's Assist Mode Special | Game Maker's Toolkit (2018) by Mark Brown. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NInNVEHj_G4

Posts

Thanks for this interesting piece. I would like to highlight a few aspects with regard to JRPGs, since you mainly wrote about action-oriented games (and I will also write about the non-JRPG RPGs that are one reason why I only play JRPGs nowadays).

Being an advocate of the "one true difficulty dogma", I really don't like it when games feature different difficulty modes, and sometimes this is the sole reason for me to not play the game in question. Since I like to refer to myself as a veteran JRPG player, I'm always compelled to choose the highest difficulty setting. Like you said, it's ridiculous to force this decision on the player at the very beginning without sufficient information.

Two examples: Romancing Monarchy's highest difficulty setting just forces the player to grind a few hours more, and that felt so unrewarding that I switched to the lowest difficulty setting just to get the game over with. Conversely, when it comes to JRPGs made by EXE-Create for Kemco, I know beforehand (from experience) that the highest difficulty setting is the one for me, because it offers higher rewards (more EXP and Gold etc.) and the exact right amount of challenge. Trust and experience can make all the difference when it comes to choosing a suitable difficulty setting. Regrettably, most times higher difficulty setting only means higher enemy stats. There are too few games that offer more interesting takes on how to design a higher difficulty setting (e.g. by granting a boss a new skill only on the highest difficulty setting).

Consequently, I'm not a fan of dynamic difficulty adjustment. Even worse, I don't play JRPGs that resort to level-scaling. What's the point of fighting and leveling up if the player doesn't get (significantly) stronger compared to the monsters? Some JRPGs that utilize level-scaling are even completely broken, effectively preventing high-leveled players from overcoming certain game segments. Even when level-scaling isn't that badly implemented, it ruins the experience for me. Why should I, for example, level up a character in Diablo 2 to level 99 if he - because of the level-scaling - still dies in one hit on the highest difficulty setting? RPGs and dynamic difficulty adjustment just don't mesh, all the more so as JRPGs in particular should always enable the player to choose a "brute force path", for it has always been characteristic of JRPGs that players can use effort to make up for their lack of skill (except for when it comes to the most difficult optional bosses).

Concerning your "ELS", I can live with such an approach as long as the player isn't patronized of forced to abandon his/her playstyle. A positive example would be an optional arena challenge during which the player can't use certain skills or equipment pieces. Ranking systems, on the other hand, tend to annoy me, especially when they're applied to battles. Instead of punishing (or not rewarding) players that don't discover or don't want to use the most broken combos, developers should let the players play how they want to play. I for one don't want to hear "You don't play as intended" or "You could play so much better" all the time. Another issue is that most ranking systems also reward speed, which is incompatible with thorough exploration encouraged by most (good) JRPGs. I still remember that I searched for secret passages in every nook and cranny when I played Wolfenstein for SNES, and that I still couldn't obtain the highest rating simply because it took me too long. Where's the fun in that? Why not offer optional new game plus only challenges instead? Even better: Let the player handle his/her own self-imposed challenges. Maybe I'm getting old, but I think being pressed for time when playing JRPGs isn't fun. The only example of an excellent rating system in a JRPG of which I can think off the top of my hat would be the dungeon completion rating system in Lakria Legends, and even that system wouldn't have been to my liking if the developer had stuck with his original idea of making completion speed part of the rating.

In short, it's a very complex topic. Since I'm a (moderate) completionist and sometimes even a powergamer, and since I also like grinding in general, I forgive most JRPGs for being too easy. On the other hand, I shy away from a game when my completionist/powergamer approach is the bare minimum to beat said game. Balancing is one of the most difficult tasks when developing a JRPG, and I don't envy the developers that need to repeat dozens of boss fights using dozens of different setups just to ensure an enjoyable gaming experience, but I always appreciate it when a developer gets the difficulty just right.

Being an advocate of the "one true difficulty dogma", I really don't like it when games feature different difficulty modes, and sometimes this is the sole reason for me to not play the game in question. Since I like to refer to myself as a veteran JRPG player, I'm always compelled to choose the highest difficulty setting. Like you said, it's ridiculous to force this decision on the player at the very beginning without sufficient information.

Two examples: Romancing Monarchy's highest difficulty setting just forces the player to grind a few hours more, and that felt so unrewarding that I switched to the lowest difficulty setting just to get the game over with. Conversely, when it comes to JRPGs made by EXE-Create for Kemco, I know beforehand (from experience) that the highest difficulty setting is the one for me, because it offers higher rewards (more EXP and Gold etc.) and the exact right amount of challenge. Trust and experience can make all the difference when it comes to choosing a suitable difficulty setting. Regrettably, most times higher difficulty setting only means higher enemy stats. There are too few games that offer more interesting takes on how to design a higher difficulty setting (e.g. by granting a boss a new skill only on the highest difficulty setting).

Consequently, I'm not a fan of dynamic difficulty adjustment. Even worse, I don't play JRPGs that resort to level-scaling. What's the point of fighting and leveling up if the player doesn't get (significantly) stronger compared to the monsters? Some JRPGs that utilize level-scaling are even completely broken, effectively preventing high-leveled players from overcoming certain game segments. Even when level-scaling isn't that badly implemented, it ruins the experience for me. Why should I, for example, level up a character in Diablo 2 to level 99 if he - because of the level-scaling - still dies in one hit on the highest difficulty setting? RPGs and dynamic difficulty adjustment just don't mesh, all the more so as JRPGs in particular should always enable the player to choose a "brute force path", for it has always been characteristic of JRPGs that players can use effort to make up for their lack of skill (except for when it comes to the most difficult optional bosses).

Concerning your "ELS", I can live with such an approach as long as the player isn't patronized of forced to abandon his/her playstyle. A positive example would be an optional arena challenge during which the player can't use certain skills or equipment pieces. Ranking systems, on the other hand, tend to annoy me, especially when they're applied to battles. Instead of punishing (or not rewarding) players that don't discover or don't want to use the most broken combos, developers should let the players play how they want to play. I for one don't want to hear "You don't play as intended" or "You could play so much better" all the time. Another issue is that most ranking systems also reward speed, which is incompatible with thorough exploration encouraged by most (good) JRPGs. I still remember that I searched for secret passages in every nook and cranny when I played Wolfenstein for SNES, and that I still couldn't obtain the highest rating simply because it took me too long. Where's the fun in that? Why not offer optional new game plus only challenges instead? Even better: Let the player handle his/her own self-imposed challenges. Maybe I'm getting old, but I think being pressed for time when playing JRPGs isn't fun. The only example of an excellent rating system in a JRPG of which I can think off the top of my hat would be the dungeon completion rating system in Lakria Legends, and even that system wouldn't have been to my liking if the developer had stuck with his original idea of making completion speed part of the rating.

In short, it's a very complex topic. Since I'm a (moderate) completionist and sometimes even a powergamer, and since I also like grinding in general, I forgive most JRPGs for being too easy. On the other hand, I shy away from a game when my completionist/powergamer approach is the bare minimum to beat said game. Balancing is one of the most difficult tasks when developing a JRPG, and I don't envy the developers that need to repeat dozens of boss fights using dozens of different setups just to ensure an enjoyable gaming experience, but I always appreciate it when a developer gets the difficulty just right.

Thanks for the thoughtful reply, Kyle. I wrote this piece originally for Gamasutra, so the concepts laid out above do tend to spread out across many genres. I do believe they apply (and have applied) very well to RPGs too. The easiest example in JRPGs I can think of off the top of my head would be the soft-lock idea where, instead of locking players out of areas that are not really "intended" for them at this point, they discourage players from venturing into those areas by putting way high level monsters in there. The most recent JRPG I've seen this being done in is Dragon Quest XI.

However, as I have implied in many different ways throughout my article, when you design your RPGs with soft-locks, that means you also have to account for that subset of players who do whatever they can to break the conventional approach. But once you've prepared for that, the line between conventional and unconventional quickly blurs out, because each approach is catered to a different subset of the audience anyway.

Perhaps I didn't elaborate my points on the ELS very well to communicate to the RPG genre. But the main idea of it is so that people DON'T ever feel patronized for taking the easy way nor compelled to do it the hard way. When applied to JRPGs, this means that games should give some leeways for people who don't have it in them, while at the same time strive to encourage people in some ways to deviate from the conventional approach or the "intended experience", instead of locking them in completely. Ideas like the area soft-locks and using Heal on Undead enemies and so on and all very clever. All of these can be done within the same difficulty mode and the same playthrough. This is nothing new as we all know, but the point of the ELS is to serve as a model to quickly outdate both the concepts of difficulty modes and DDA, and also as a sort of design philosophy.

However, as I have implied in many different ways throughout my article, when you design your RPGs with soft-locks, that means you also have to account for that subset of players who do whatever they can to break the conventional approach. But once you've prepared for that, the line between conventional and unconventional quickly blurs out, because each approach is catered to a different subset of the audience anyway.

Perhaps I didn't elaborate my points on the ELS very well to communicate to the RPG genre. But the main idea of it is so that people DON'T ever feel patronized for taking the easy way nor compelled to do it the hard way. When applied to JRPGs, this means that games should give some leeways for people who don't have it in them, while at the same time strive to encourage people in some ways to deviate from the conventional approach or the "intended experience", instead of locking them in completely. Ideas like the area soft-locks and using Heal on Undead enemies and so on and all very clever. All of these can be done within the same difficulty mode and the same playthrough. This is nothing new as we all know, but the point of the ELS is to serve as a model to quickly outdate both the concepts of difficulty modes and DDA, and also as a sort of design philosophy.

Really enjoyed this article and it really made me think about difficulty. Very well constructed and very informative.

However, I don't think there's enough here to spell a death knell for difficulty modes, especially in RPGs, unless I'm really missing something. There are players who simply want a more casual experience, and don't want to have to completely master the system or trial-and-error classes to find which ones are easiest. If making the game easier for the player costs them hours of banging their head against the game's systems to see what works when they just wanted to have a leisurely playthrough, less comfortable players will quit the game. Some of them just want an easy way to pick up the game and play, and I think a lot of what's being discussed here doesn't really help them.

I understand that difficulty modes are an inelegant solution to the problem, but there's no one size-fits-all difficulty for any game, and I'd much rather have players be able to tweak the game's difficulty than quitting in frustration.

That's not to say that we shouldn't be looking for better solutions and trying new things. I just personally don't think game difficulty options in RPGs is as terrible as its often made out to be.

However, I don't think there's enough here to spell a death knell for difficulty modes, especially in RPGs, unless I'm really missing something. There are players who simply want a more casual experience, and don't want to have to completely master the system or trial-and-error classes to find which ones are easiest. If making the game easier for the player costs them hours of banging their head against the game's systems to see what works when they just wanted to have a leisurely playthrough, less comfortable players will quit the game. Some of them just want an easy way to pick up the game and play, and I think a lot of what's being discussed here doesn't really help them.

I understand that difficulty modes are an inelegant solution to the problem, but there's no one size-fits-all difficulty for any game, and I'd much rather have players be able to tweak the game's difficulty than quitting in frustration.

That's not to say that we shouldn't be looking for better solutions and trying new things. I just personally don't think game difficulty options in RPGs is as terrible as its often made out to be.

Sooz

They told me I was mad when I said I was going to create a spidertable. Who’s laughing now!!!

5354

The thesis seems to be, at least partly, that difficulty modes are Bad because they're not a significant choice for the player, which strikes me as a silly thing to say. What color windowframe or what costume elements I wear don't generally have any effect at all on the game itself, and I'm not weighing the upsides and downsides of the cat ears versus the beret, but I still find them valuable elements to the game.

Similarly, if a game allows me to choose difficulty, I find that a valuable element because, y'know, sometimes I don't WANT to play like a True Hardcore Gamer. Sometimes, I want to breeze through and have some fun for once in my miserable existence without having to figure out the One True Perfect Speedrun 100% Perfect way to play is.

ETA: Also I am not sure why your ELS scale is putting "game pretty" as the opposite of "game easy."

Similarly, if a game allows me to choose difficulty, I find that a valuable element because, y'know, sometimes I don't WANT to play like a True Hardcore Gamer. Sometimes, I want to breeze through and have some fun for once in my miserable existence without having to figure out the One True Perfect Speedrun 100% Perfect way to play is.

ETA: Also I am not sure why your ELS scale is putting "game pretty" as the opposite of "game easy."

A good example for myself would be been I begin a Fallout New Vegas game I like to play on Hardcore and Very Hard difficulty. Having played the game so much, that's where I like to start these days. I would really dislike it if I couldn't do that at the very beginning.

And, I can't stop watching the Spy Master gif

And, I can't stop watching the Spy Master gif

Huge issue with Dark Souls and the Organic Difficulty proposition: It's really just similar to the issues of the others. Picking Pyromancer at the start of Dark Souls is really just a hidden easy mode aka a choice from the very start. Someone going into the game for the first time wants to RP as Gandalf when they pick magic, not to "organically" take it easy. To me that whole thing was just incidental, and Demon's Souls (the game before it) took more of the route of different parts are difficult for different builds. I don't think making the game simply imbalanced from the very start (most AI unable to deal with ranged hitstun attacks, the magic system being spam to win, ignoring every combat mechanic ) is the most elegant solution. Not to mention the magic system is actually cumbersome to use for any new player. There's a lot of things in Dark Souls that aren't exactly... elegant. It's just an imbalanced game lol.

To broadly address optional rankings and encouraging speedrunning as an optional difficulty... this like affects like 2-3% of your playerbase. Keep that in mind, I would spend a ton of development time making "Challenge Levels" for one particular game that were unlocked by speed running and collecting. A lot of time was put into them but they ended up not being worth their existence in the end (according to achievements). The battle of finding a gameplay difficulty for everyone is rather fruitless when considering the war of finding gameplay people actually want to play is a greater thing to consider.

You've lost me on the Ludoaesthetics section. Game design academia really isn't my bag.

To broadly address optional rankings and encouraging speedrunning as an optional difficulty... this like affects like 2-3% of your playerbase. Keep that in mind, I would spend a ton of development time making "Challenge Levels" for one particular game that were unlocked by speed running and collecting. A lot of time was put into them but they ended up not being worth their existence in the end (according to achievements). The battle of finding a gameplay difficulty for everyone is rather fruitless when considering the war of finding gameplay people actually want to play is a greater thing to consider.

You've lost me on the Ludoaesthetics section. Game design academia really isn't my bag.

Dark Souls is always an interesting reference for difficulty. I think the reason people initially find it challenging is because nothing that came before it (aside from Demon Souls obviously) played anything like it. The difficulty comes from not understanding how it works because its so alien, not from the gameplay itself. Just like any other genre, once you know how to play these games they are an absolute cakewalk. A souls title is only hard the first time you play it.

Thanks for the replies, everybody. Your thoughts are all interesting and made me think a lot more about this. I'm glad I shared with you RPG folks.

Thanks for the kind words, unity. A lot of the concerns you addressed are exactly the reason for this model. But perhaps I didn't elaborate it clearly enough to easily apply to RPGs. People looking for the casual experience ARE on the Effectiveness side of the spectrum. I made an effort to put an entire section to the other end of the spectrum simply because it's more often overlooked. In no way did I mean there wasn't room for casual players. It's a spectrum for reason.

What I'm saying can be basically translated into the RPG language as something like these:

As I've mentioned throughout the article as well as in my comments above, this model is to serve exactly this purpose.

I'm also not sure why you're confused as to why "game pretty" can't be the opposite of "game easy." People deliberately forgo high level equipment all the time just because they like the looks of a lower level equipment set better. Or people ignore high level skills all the time just because the lower level skills have higher combo count, which can help them break their own combo count record, which serves absolutely no purpose besides unlocking achievements or simple bragging rights. You can find these in every Tales game ever.

Truthfully I don't see how it's not an elegant solution. I'm not saying the intended experience for Dark Souls is melee. But it's just the way it chooses to be, that those who pick melee will have a harder time in the game, and those who pick range or magic will have an easier time. You could very well make a game where those two are reversed. It is true that Dark Souls is an unbalanced game, and intentionally so. In the end, the whole point of this imbalance is so that players of different skill levels can enjoy the game in the best possible way without all the downsides of the traditional approach to difficulty.

You are most likely correct in pointing out that only a small subset of the playerbase would ever attempt speedrunning. But my point with that example is two fold:

author=unity

However, I don't think there's enough here to spell a death knell for difficulty modes, especially in RPGs, unless I'm really missing something. There are players who simply want a more casual experience, and don't want to have to completely master the system or trial-and-error classes to find which ones are easiest. If making the game easier for the player costs them hours of banging their head against the game's systems to see what works when they just wanted to have a leisurely playthrough, less comfortable players will quit the game. Some of them just want an easy way to pick up the game and play, and I think a lot of what's being discussed here doesn't really help them.

Thanks for the kind words, unity. A lot of the concerns you addressed are exactly the reason for this model. But perhaps I didn't elaborate it clearly enough to easily apply to RPGs. People looking for the casual experience ARE on the Effectiveness side of the spectrum. I made an effort to put an entire section to the other end of the spectrum simply because it's more often overlooked. In no way did I mean there wasn't room for casual players. It's a spectrum for reason.

What I'm saying can be basically translated into the RPG language as something like these:

- To support the more casual players, instead of using difficulty modes, perhaps you can try immediately giving them a leg up with the option to obtain easy-mode-exclusive items that give them some moderate advantages: A ring that reduces all incoming damage. A ticket that lets players save anywhere instead of having to reach a save point. A lantern you can buy at any town which reduce the stats of all bosses by 30%. These are all ideas for an organic easy mode that is not a menu-based option. The point is to stop thinking of them as imbalance factors.

- To support people who seek challenge by arranging things in such a way that hints at the possibility of an unconventional yet elegant approach. Think of something like FF8 allowing players to obtain Squall's Lion Heart right from Disc 1. It's possible, just incredibly tedious and difficult.

author=Sooz

Similarly, if a game allows me to choose difficulty, I find that a valuable element because, y'know, sometimes I don't WANT to play like a True Hardcore Gamer. Sometimes, I want to breeze through and have some fun for once in my miserable existence without having to figure out the One True Perfect Speedrun 100% Perfect way to play is.

ETA: Also I am not sure why your ELS scale is putting "game pretty" as the opposite of "game easy."

As I've mentioned throughout the article as well as in my comments above, this model is to serve exactly this purpose.

I'm also not sure why you're confused as to why "game pretty" can't be the opposite of "game easy." People deliberately forgo high level equipment all the time just because they like the looks of a lower level equipment set better. Or people ignore high level skills all the time just because the lower level skills have higher combo count, which can help them break their own combo count record, which serves absolutely no purpose besides unlocking achievements or simple bragging rights. You can find these in every Tales game ever.

author=Darken

Huge issue with Dark Souls and the Organic Difficulty proposition: It's really just similar to the issues of the others. Picking Pyromancer at the start of Dark Souls is really just a hidden easy mode aka a choice from the very start. Someone going into the game for the first time wants to RP as Gandalf when they pick magic, not to "organically" take it easy. To me that whole thing was just incidental, and Demon's Souls (the game before it) took more of the route of different parts are difficult for different builds. I don't think making the game simply imbalanced from the very start (most AI unable to deal with ranged hitstun attacks, the magic system being spam to win, ignoring every combat mechanic ) is the most elegant solution. Not to mention the magic system is actually cumbersome to use for any new player. There's a lot of things in Dark Souls that aren't exactly... elegant. It's just an imbalanced game lol.

Truthfully I don't see how it's not an elegant solution. I'm not saying the intended experience for Dark Souls is melee. But it's just the way it chooses to be, that those who pick melee will have a harder time in the game, and those who pick range or magic will have an easier time. You could very well make a game where those two are reversed. It is true that Dark Souls is an unbalanced game, and intentionally so. In the end, the whole point of this imbalance is so that players of different skill levels can enjoy the game in the best possible way without all the downsides of the traditional approach to difficulty.

You are most likely correct in pointing out that only a small subset of the playerbase would ever attempt speedrunning. But my point with that example is two fold:

- Speedrunning is only ONE of the manifestations of arbitrary, self-imposed challenges with intrinsic values to players. By using speedrunning as an example I do not at all mean all games should be designed to be speedrun. That is just silly.

- The reason why the ELS model is a spectrum is only because I wanted to emphasize the gradation of all subject matters within a game. How far and wide the spectrum can be depends greatly on how much effort you are willing to put in to stretch it. If you don't want to spend your effort on designing your game to support speedrun, that's fine. All the power to you. But there are a ton of smaller things you can do with minimal effort to stretch this spectrum.

author=Darken

The battle of finding a gameplay difficulty for everyone is rather fruitless when considering the war of finding gameplay people actually want to play is a greater thing to consider.

You're absolutely right. Surprisingly, most of the JRPGs offering different difficulty modes that I've played these past years didn't shine in terms of overall gameplay. They simply weren't excellent JRPGs, and that's possibly why I associate different difficulty modes with subpar game design. This might be a totally unfair assumption, but it helps me to find the games that I enjoy the most. I have nothing against casual experiences; in fact it was a blessing that I could switch to a casual experience while playing Romancing Monarchy (mentioned in my previous post), because otherwise I definitely would have quit.

There are also other genres/games where I enjoy a casual experience from time to time, for example playing GTA San Andreas using a save file in which a more skillful player already obtained all optional stuff for me, so that I can breeze through the main campaign. Also, I played the first JRPG made by EXE-Create for Kemco that was released on Steam on the lowest difficulty setting, since I wanted to become familiar with the game's structure, especially the battle system (EXE-Create's JRPGs, which are firstly and primarily released on mobile platforms, are a clear case of "if you've played one, you've played them all", which makes all of them fun for people who like how these games are structured). Now I enjoy them on the highest difficulty setting, while I can at the same time understand anyone who "only" wants to play them on the lowest difficulty setting. One of the more recent EXE-Create games, Antiquia Lost, did something interesting, by the way. The hardest optional dungeon was available early (only a few hours into the main storyline), so it was possible to challenge it and grind there until level 999, which made the rest of the game very easy (and of course I couldn't resist).

This is what JRPGs should be about, and EvilEagles already stressed it: Giving players the tools to overcome any challenge thrown at them. JRPGs can offer so many opportunities to do exactly that (grinding, hidden treasure, completing side quests, adjusted setup/strategy when battling bosses), so I still think a well-designed JRPG only needs "one true difficulty", since most games already take different skill levels and learning curves into consideration (tutorial at the beginning, optional superbosses at the end etc.).

What I'm trying to say using too many words is: A well-designed game knows how to handle difficulty (different difficulty modes are not suitable for every game), and if a well-designed game offers different difficulty modes, the game is an enjoyable experience on all of them. To draw a line from this wall of text to Darken's quote at the beginning: It isn't (only) the right difficulty that makes a game good, instead good games get the difficulty right. Nevertheless, a game offering different difficulty modes is still less likely to draw my attention than a game without difficulty settings. It's a matter of experience, and if in doubt, experience/gut feeling still prevails, despite how flawed our own perception can be.

Sooz

They told me I was mad when I said I was going to create a spidertable. Who’s laughing now!!!

5354

As I've mentioned throughout the article as well as in my comments above, this model is to serve exactly this purpose.

I mean, not really? Like, it's a bit difficult to tell what you're proposing, beyond "Do good design, not bad design, also explicit choice of difficulty is bad design because reasons."

What I'm saying is, sometimes, I like to play hardcore, and sometimes I just want to dick around, and in both cases, I prefer to be allowed explicitly to choose what level I'm doing, rather than having to guess at things or trust the dev to have been able to predict how I play. Forcing difficulty to be part of the gameplay (somehow) is forcing the player to 1) figure out that the difficulty is part of the gameplay and not just totally static, and B) figure out how to alter the difficulty to their taste according to the whims of an unknown developer.

I don't think there's a perfect silver bullet to make difficulty levels suit every player; conversely, I also don't think that having elements separate from the gameplay are necessarily bad for Flow or enjoyment. (TBH it feels like that stuff is treated like garlic for vampires these days, rather than just one of many options. It's silly, especially when designing for an already low-fi medium like RPG Maker games.)

author=EvilEagles

I'm also not sure why you're confused as to why "game pretty" can't be the opposite of "game easy." People deliberately forgo high level equipment all the time just because they like the looks of a lower level equipment set better. Or people ignore high level skills all the time just because the lower level skills have higher combo count, which can help them break their own combo count record, which serves absolutely no purpose besides unlocking achievements or simple bragging rights. You can find these in every Tales game ever.

Aight but what does that have to do with "visual and auditory appeal of using the subject matter or the subject matter itself"? Like, yeah, people often use the pretty equipment over the functional equipment when that's a thing, but it doesn't work so much as an inherent duality. You'll just as often find that the best equipment also looks the best, or find that equipment doesn't vary in aesthetics, for example. It just strikes me as a false duality, is all, since the design of stuff is independent of the use of stuff.

author=EvilEagles

Thanks for the replies, everybody. Your thoughts are all interesting and made me think a lot more about this. I'm glad I shared with you RPG folks.

author=unity

However, I don't think there's enough here to spell a death knell for difficulty modes, especially in RPGs, unless I'm really missing something. There are players who simply want a more casual experience, and don't want to have to completely master the system or trial-and-error classes to find which ones are easiest. If making the game easier for the player costs them hours of banging their head against the game's systems to see what works when they just wanted to have a leisurely playthrough, less comfortable players will quit the game. Some of them just want an easy way to pick up the game and play, and I think a lot of what's being discussed here doesn't really help them.

Thanks for the kind words, unity. A lot of the concerns you addressed are exactly the reason for this model. But perhaps I didn't elaborate it clearly enough to easily apply to RPGs. People looking for the casual experience ARE on the Effectiveness side of the spectrum. I made an effort to put an entire section to the other end of the spectrum simply because it's more often overlooked. In no way did I mean there wasn't room for casual players. It's a spectrum for reason.

What I'm saying can be basically translated into the RPG language as something like these:

- To support the more casual players, instead of using difficulty modes, perhaps you can try immediately giving them a leg up with the option to obtain easy-mode-exclusive items that give them some moderate advantages: A ring that reduces all incoming damage. A ticket that lets players save anywhere instead of having to reach a save point. A lantern you can buy at any town which reduce the stats of all bosses by 30%. These are all ideas for an organic easy mode that is not a menu-based option. The point is to stop thinking of them as imbalance factors.

- To support people who seek challenge by arranging things in such a way that hints at the possibility of an unconventional yet elegant approach. Think of something like FF8 allowing players to obtain Squall's Lion Heart right from Disc 1. It's possible, just incredibly tedious and difficult.

Thank you very much for clarifying! ^_^

Do you suggest labeling these things as in-game easy modes? Otherwise, I can see some players using them even when they don't need them and then complaining that the game is too easy. I know that seems counter-intuitive, but do you just tell them "then just don't use that item?" Or do you discourage them from asking by putting something in the description like "for players who struggle with combat" or something in the description?

Sooz

They told me I was mad when I said I was going to create a spidertable. Who’s laughing now!!!

5354

author=unity

I can see some players using them even when they don't need them and then complaining that the game is too easy.

Or, contrariwise, dumbasses like me who never figure out that those things are supposed to be for the kindergarten baby gamers, and give up in frustration because we never figure out the easy mode.

author=Sooz

I mean, not really? Like, it's a bit difficult to tell what you're proposing, beyond "Do good design, not bad design, also explicit choice of difficulty is bad design because reasons."

What I'm saying is, sometimes, I like to play hardcore, and sometimes I just want to dick around, and in both cases, I prefer to be allowed explicitly to choose what level I'm doing, rather than having to guess at things or trust the dev to have been able to predict how I play. Forcing difficulty to be part of the gameplay (somehow) is forcing the player to 1) figure out that the difficulty is part of the gameplay and not just totally static, and B) figure out how to alter the difficulty to their taste according to the whims of an unknown developer.

I don't think there's a perfect silver bullet to make difficulty levels suit every player; conversely, I also don't think that having elements separate from the gameplay are necessarily bad for Flow or enjoyment. (TBH it feels like that stuff is treated like garlic for vampires these days, rather than just one of many options. It's silly, especially when designing for an already low-fi medium like RPG Maker games.)

I did elaborate pretty explicitly in my comments above. I respectfully urge you to read them before continuing this line of discussion. Like I said, I wrote this piece originally for a different audience, so it might not be as catered to RPGs as you folks might expect here. But that's why I clarified further.