THE SOUND OF GAME MAKE

Wherein I discuss how I make music...hopefully in a way that helps you.

pianotm

pianotm- 03/11/2021 11:18 PM

- 2939 views

Some time ago, I was asked by Liberty to write an article explaining how to write music. So I said, “No problem,” and got right to work. Then as I was writing the article, I realized, OH! I'm not just going to be able to explain this. So, my family has a saying, “The only way to eat an elephant is one bite at a time.” So, in telling people on the other side of a monitor how to make music for their video games, I have a full elephant set out before me, and nothing but a fork and steak knife to dig in with. So, let the meal begin.

This assumes that you are a beginner.

This is not an epic course like Slip Into Ruby. This is fast and dirty, and will be making assumptions about your ability to hear patterns.

There are so many considerations when thinking about what you want your video game to sound like. Is it going to sound like the 8-bit trashterpieces of the golden age of Atari, Intellivision, or Spectrum ZX? Just how retro do you want your music to be? Do you want it to be an orchestral masterpiece that would make Nobuo Uematsu feel inadequate? Well, no matter what style of music you want, you can rest assured that I am going to tell you one, specific way to make music and for anything else, you will be on your own. Why does this not matter? Because whether you're making 8-bit or realistic orchestral sounding music, it entirely depends on the sound of the instruments you're using and how much mixing and processing you want to do after you've written your song.

The Available Tools

Digital Instruments

A variety of digital equipment is available. The most common you'll be familiar with are digital keyboards and pianos, but these tend to cost several thousand dollars. The same is true of digital violins, cellos, guitars, and such. People who go into music stores get told a lot of things. “If you really want to write music, you need the best, and most versatile equipment on the market.” Let's be perfectly honest here; salespeople are absolutely full of shit. Beavis and Butthead know more about getting laid than a salesperson knows about what you need. Rest assured you can do exactly everything and much more than with the Roland Fantom, or the latest Alesis that's going to set you back 20 or 30 thousand dollars that the salesperson is telling you about. Do you know what else can do absolutely everything that that Roland Fantom, Alesis, Korg Trinitron, or Kawaii Z-1000 can do? Your computer and a 200 dollar MIDI controller. And realistically, you don't even need the MIDI controller unless you're using a Digital Audio Workspace, or DAW.

To be fair, many DAWs don't require you to have a MIDI controller, but they're not very easy to figure out without one. DAWs are programs that essentially function as full music studios. Once you've learned how to use one, you can make some amazing music. For these articles, though, forget about DAWs because we're going as basic as possible. DAWs give you versatility as a musician, but they're not necessary, and the only reason I'm telling you this is because I'm trying to give you easy routes to learning how to write music. DAWs require a lot of experience as a musician and I am frankly assuming you're a beginner if you're reading this.

I don't use a DAW for the music I have publicly released and I think my music is pretty alright. I do use a DAW. I use Reaper. But everything I've done on it is experimental and I don't spend a lot of time with it. So, what can you use if you don't need a DAW? Well, there are a number of freewares available that can help you make quality music. Musescore 3 is free notation software that is capable of composing full orchestral scores and it is my preferred program. If you don't feel comfortable with notation, then your other option is software that uses piano roll writing. The most popular freeware for that is LMMS.

Soundfonts and Virtual Studio Technology

So, let's start with Virtual Studio Technology, or VSTs. A VST is a plugin. It contains a set of instruments, such as different styles of guitars or different pianos. Upon uploading to software, it adds a widget that gives you the VST's own control panel that controls its soundfont. I don't know if LMMS uses them, but this is the only time I will be mentioning VSTs since the program I work in doesn't use them. You've likely noted that VSTs contain a soundfont. Musescore 3 only requires soundfonts directly uploaded to its sound file. Try out both Musescore and LMMS, or any other studio you have and see which one you prefer.

Soundfonts, as the name implies, are the sounds themselves. VSTs have soundfonts installed in them, but you don't really need VSTs with the more basic notation software. Soundfonts are libraries of sounds. Some of them have full orchestras. Musescore comes with a soundfont that contains a full orchestra, a full synthesizer set, and dozens of ethnic instruments whose names you can't pronounce. Other soundfont libraries are available online. You can use them by downloading, unzipping, and dropping the file directly in Musescore's sound folder. Once it's in, you'll be able to access the new soundfont in Musescore's synthesizer selection in its View menu. Simply tick the synthesizer box and it will open a window that shows you the available soundfonts. Move the one you want to use to the top of the list. On every boot of Musescore, you'll need to do this since the system always starts with the default on top. If you want the new soundfont to be the default, simply move it to the top of the list and press the “default” button.

Now what do you do?

Play with it. Forget learning how to write music for a while and play with the sounds you can make with this software. You probably have about 200 instruments at your disposal right now. Add channels or staffs and make as many varied noises as you can. Go wild. Get silly. Let me help you identify some stuff to help you maximize your tomfoolery:

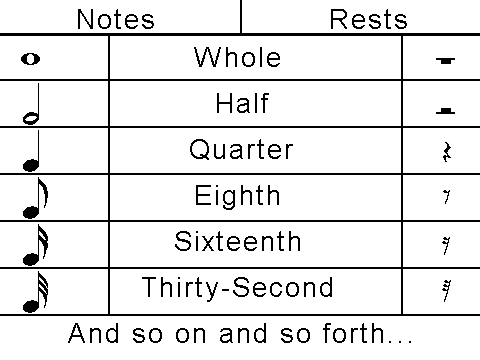

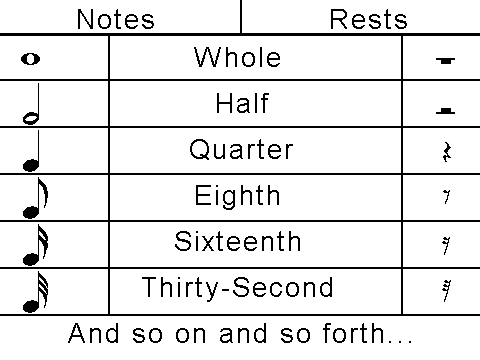

Want faster notes? Add more flags! In theory, you could add as many flags to a note as you like to keep making it faster. Practically? You're eventually going to run out of room on the sheet and if you're writing your score in 524,288/524,288, you're just going to give the listener tinnitus. And maybe a seizure (No, seriously. Google “black MIDI”. Just like flashing lights on a monitor, chaotic noise beyond a certain frequency and speed is dangerous. The military has actual weapons based on this.).

These aren't the only notes available, but they are the base note types. You can alter their speed by placing them in tuplets (tuplets divide a beat by a specified amount, a beat being the length of a quarter note in the standard 4/4 timing.)

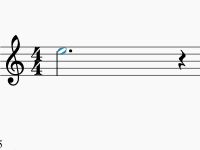

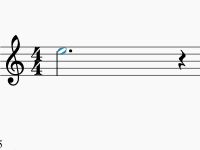

You can also alter a note's speed by adding an augmentation dot. This changes the notes speed to halfway between the dotted note and the next sized note. In the following example, the half note is turned into a three quarters note with an augmentation dot.

There are other ways to lengthen a note, such as with ties. The following example is quite literally the same note as above, simply expressed with a tie instead of an augmentation dot.

So, what are beats? Well, do you see that 4/4 at the beginning of the staff? That measures how many notes of a certain type can fit in a measure. In the expressed measure, a single whole note can fit, and nothing else. It is the long note. A half note, when expressed, lasts for half as long as a whole note (shocking, right?). A quarter note lasts for a quarter as long as whole note or half as long as a half note, and is what the 4/4 timing specifically denotes. 4 quarter notes can fit in a 4/4 measure. No more, no less. Now, you can see how music can be timed and measured. These are the beats, and in a lot of music, there's nothing audio expressing the beat, but in most music, you've usually got a drum, or a set of drums keeping time. But even when there's nothing expressing the beat, you can still hear it. If the rhythm is off on even one measure, it stands out to our ears painfully.

You can change the volume of an instrument with the dynamic selection in the left “palettes” menu. The dynamic ranges are as follows:

ppp = pianississimo (softest)

pp = pianissimo (softer)

p = piano (soft)

mp = mezzo piano (soft mid-range)

mf = mezzo forte (hard mid-range)

f = forte (hard/loud)

ff = fortissimo (harder/louder)

fff = fortississimo (hardest/loudest)

There are other dynamic ranges that I'm going to ask you not worry about. They have subtleties that as a beginner, you're not going to really be able to hear, and we're going to be able to address those subtleties anyway with another method. We are, after all, dealing with MIDI, and there are certain things that MIDI cannot do, but that's where processing will come in.

But enough serious talk. Armed with the basic knowledge I've just given you, you can be somewhat dangerous with this software. Revel in your toy. Spend hours with it. Spend days with it. Try to duplicate your favorite songs. Do a MIDI rendition of Bad Romance. Make brilliant chaos! Children make it obvious that humans learn through play, but we seem to think that play is useless once children have learned how to read and tell time. This is totally false. The best way to learn a system is by playing with it. Push all the buttons. Try out all the instruments. Make all the sounds. Make gibberish! It'll be great!

I have come from the future of this article to isolate this spot, because I feel like more than anything else I say anything in this article, following the advice in the above paragraph is the most crucial thing you can do. Play with the music. By all means, waste type making gibberish songs you think sound cool. Try and replicate your favorite pieces of music. Do the Terminator theme. Try to recreate your favorite Final Fantasy songs. Legend of Zelda. Super Mario Bros. Arrange your favorite cartoon themes. Try to do some Daft Punk. Obsess over this. This more than anything is going to help you understand how music comes together.

Want to make multiple different instruments make noise at the same time? You'll need more lines for that. Add instruments in Musescore by going to the edit menu and finding “Instruments”, or press “I” on your keyboard. You'll get a window with a list of instruments that you can add or remove.

Once you're done playing around, we can start discussing methods of music creation. We're going to begin with a bit of basic conceptualization. This is not music theory. I never studied it. This is simply an explanation of my thought processes. If any of it coincides with actual music theory, I will consider it a happy coincidence.

Pattern Seeking isn't a Bad Thing

At the most basic level when I write music, one of the things I will do is start by creating a pattern. This is the most common way I approach a new composition. I will make numerous musical patterns before finding one that really sticks with me. That could be a melody line, a bass line or a drum line. Let me immediately clarify here that this method is best described as banging on the keyboard like an idiot and seeing if I hear something like, and then taking that, isolating it, and trying to make it make musical sense. A few guidelines to employ:

Make a pattern that fits in a single measure. This doesn't have to be the 4/4 scale. If you've come up with a pattern that doesn't fit in the 4/4 time signature, don't just throw it out. See if it fits in another time signature. Caveat: the potential time signatures are infinite, but once you start to leave the common ones, it starts to get tricky. If your beat does not fit in any regular time signature, you might find yourself in irregular time signatures. If this happens, you'll have a difficult time getting the timing right. There are ways of dealing with this, but at this point, I recommend altering your musical pattern to something that fits neatly into one of the commonly used time signatures, because irregular beats can be a real headache. If ALL instrument lines you make follow that irregular beat cleanly, then it works. Go with it. If not, you're in for a rough time.

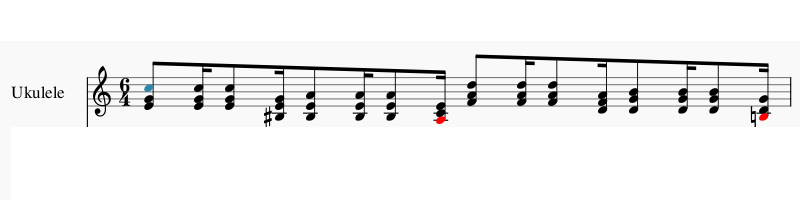

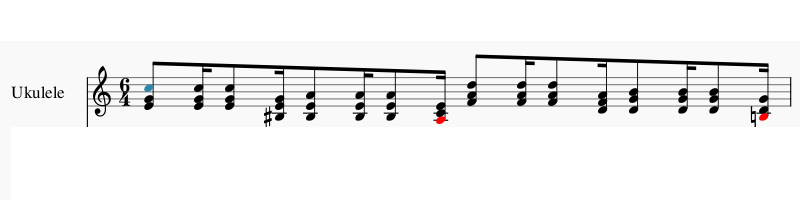

For Shell Game, I came up with a simple guitar riff and assigned a Ukulele to it. This riff dominates the entire song.

Repeat the pattern. This is video game music. With a few exceptions, it needs to loop cleanly, and repetition is going to be your best tool for making your whole song able to repeat itself.

All things in modulation. Repeat the pattern, but don't let it drone on. Modulate the key (this is when the music's notes go higher and lower). Change the notes the in the pattern at some points. Alter the pattern and have it alternate with the original pattern.

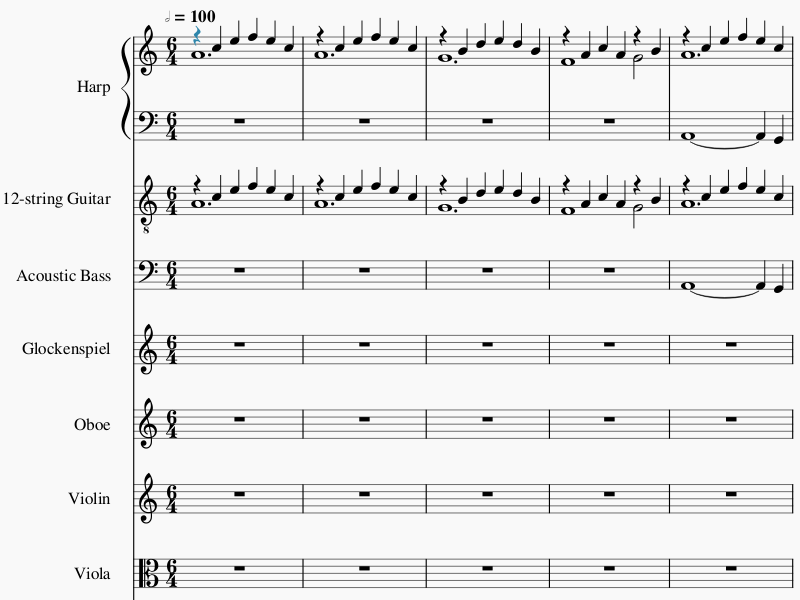

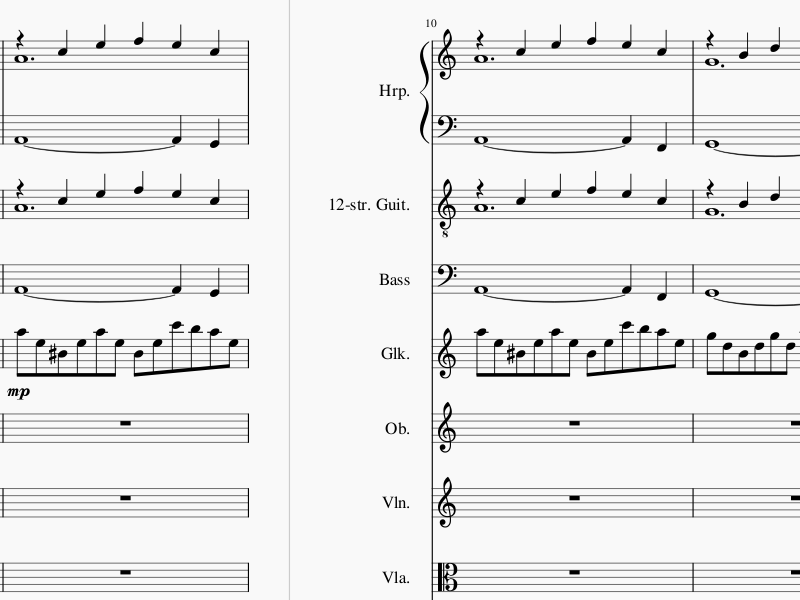

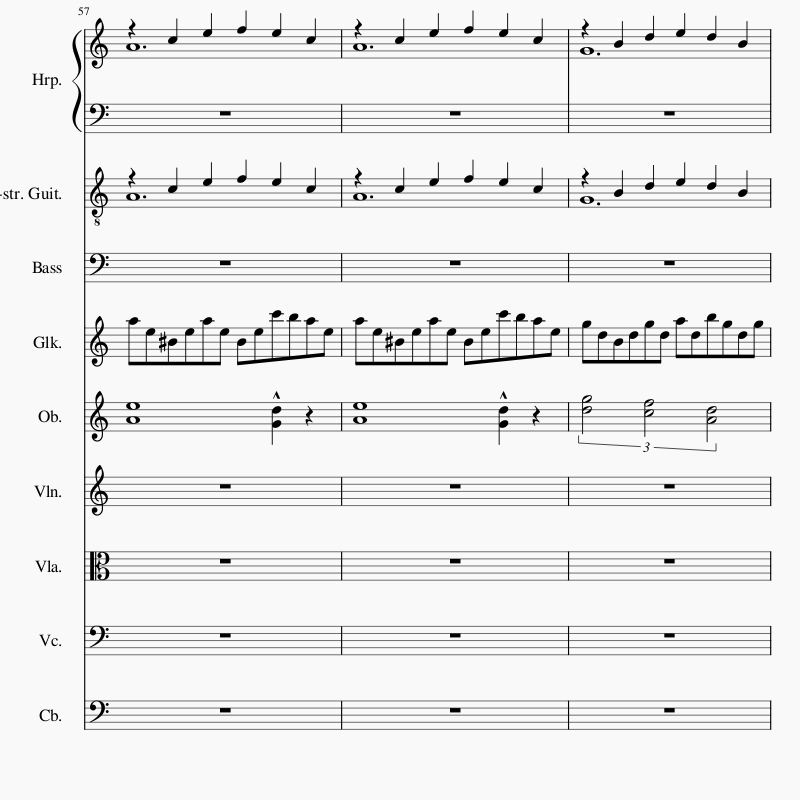

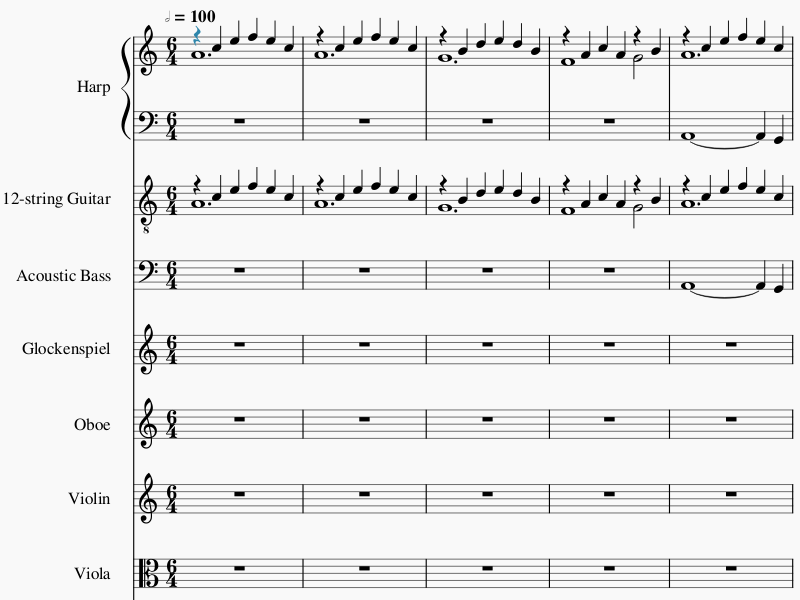

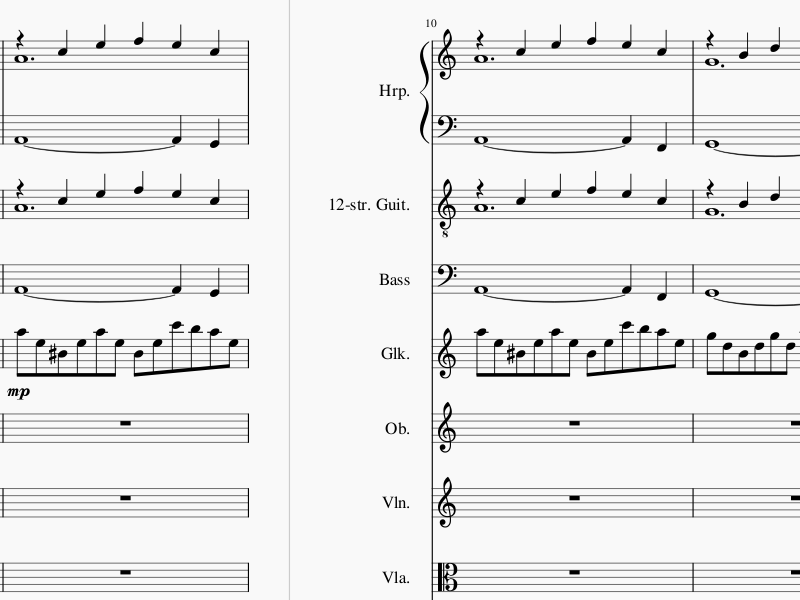

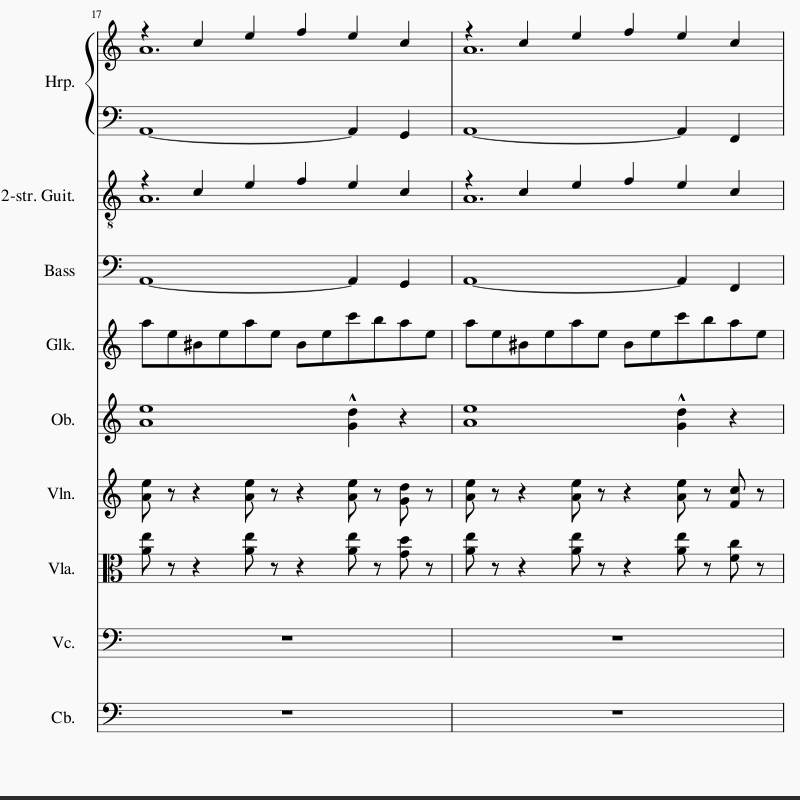

For Strange New World, my chosen pattern was a repeating arpeggio on the harp. As you can see, once I've repeated the pattern, I transpose, or modulate, down a step. You can also see that eventually, I change the note order and replace two quarters with a half note. Think of this line as a sentence. The first measure is a statement. The second measure confirms the statement. The third measure asks a question about the statement. The fourth measure offers a counterpoint to the statement. This isn't a discussion, yet. So far, we only hear one speaker. But in that fifth measure, you can see the sentence is being repeated, and a second speaker, the bass line of the harp, is chiming in with its own opinion. Basically, you see the main speaker make a point, confirm it, wonder if it's true, suggest an alternative, and then engage in conversation about that point with another speaker.

It's almost like it writes itself! I don't know how it works for other people. I can't help but think that maybe I think really strange, but when I listen to my pattern, I can sort of start to hear other instruments accompanying it, and I quickly get a very firm grasp of what my song sounds like. At this point, I write it down. I worry that maybe you're different. Whatever the case, I add instruments and I add accompaniment as I can hear it gradually come together in my imagination. This is going to get into a lengthy discussion about structure that I'm going to save for later (basically, what instruments should accompany the first one, are you even going to use the first one or change it to something else, what instruments naturally go together, don't go together, etc. etc.). Your accompaniment needs to harmonize in some way with.

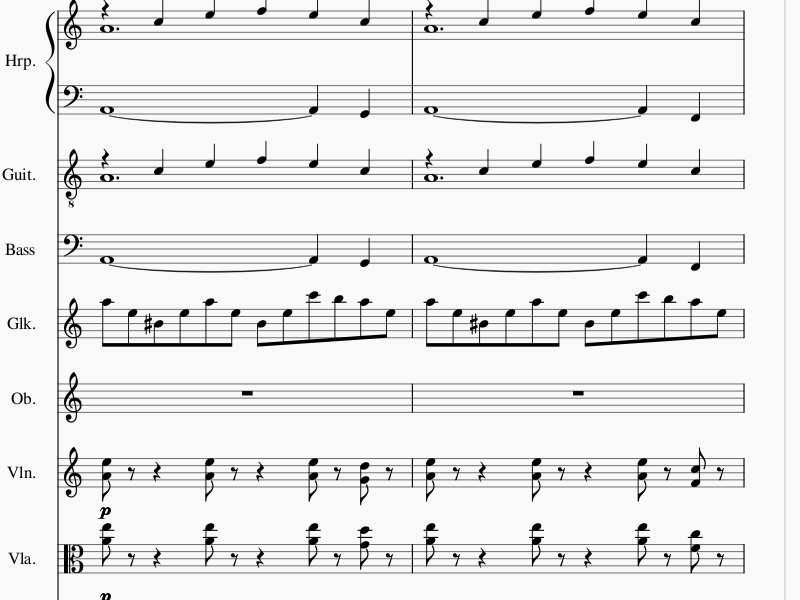

Here, you can see that in Strange New World, I reinforce my treble harp by copying it to a 12-string guitar and my bass harp with an acoustic bass. This adds a personality to the specific sound that one instrument alone wouldn't give.

The glockenspiel is not providing a melody but is adding accompanying harmony to the harp and guitars. We now have five speakers conversing harmoniously.

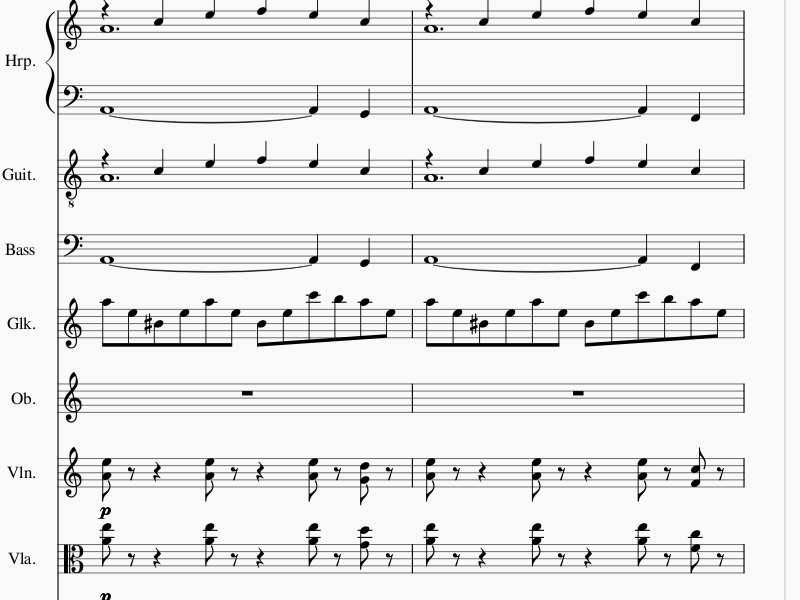

Violins and violas are now keeping time in a similar fashion to drums. In this instance, I've created a string line that adds importance and gravitas to the harmony. They are dramatically signaling that weighty matters are being discussed and that this conversation is not to be taken lightly. These strings have a staccato sound to them (even though they're not staccato) and are keeping track of the beat just as drums would. Note that I don't bring these instruments in all at once. I start the song with the harp and the guitars. They express the four measure subject once, add a bass line to the subject, repeating it again. The third time, we add a glockenspiel. The fourth time, we add strings. We are now 16 measures into the song. We've stated our point four times.

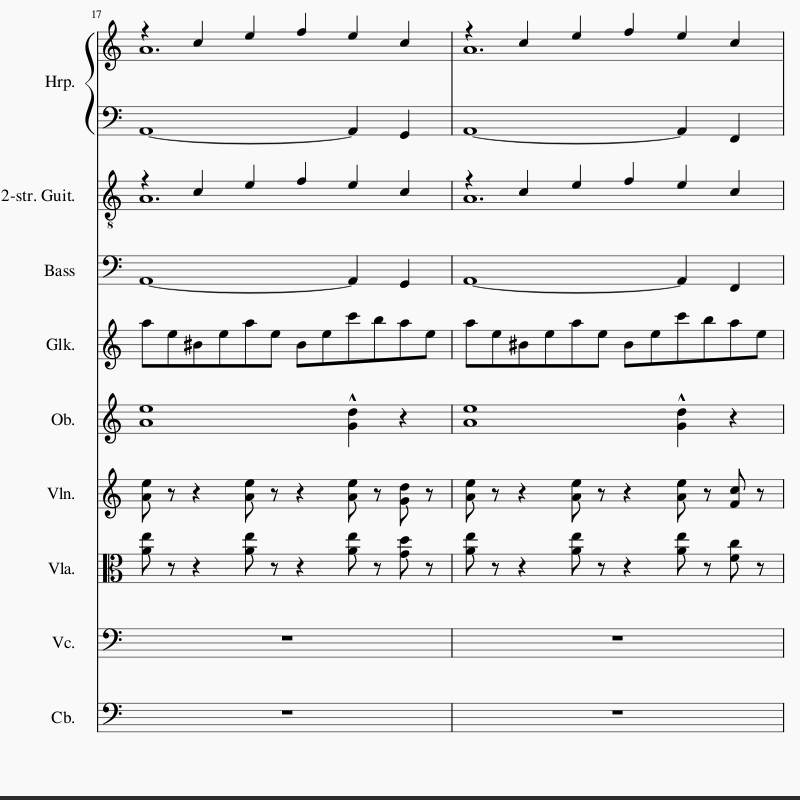

And now, at the 17th measure the oboe finally joins us. This isn't a harmonizing line. No. You can see that the oboe is saying something very different, so it's going to stand out among the rest of the speakers. This is our melody line and the oboe is the narrator of the tale this song is trying to tell.

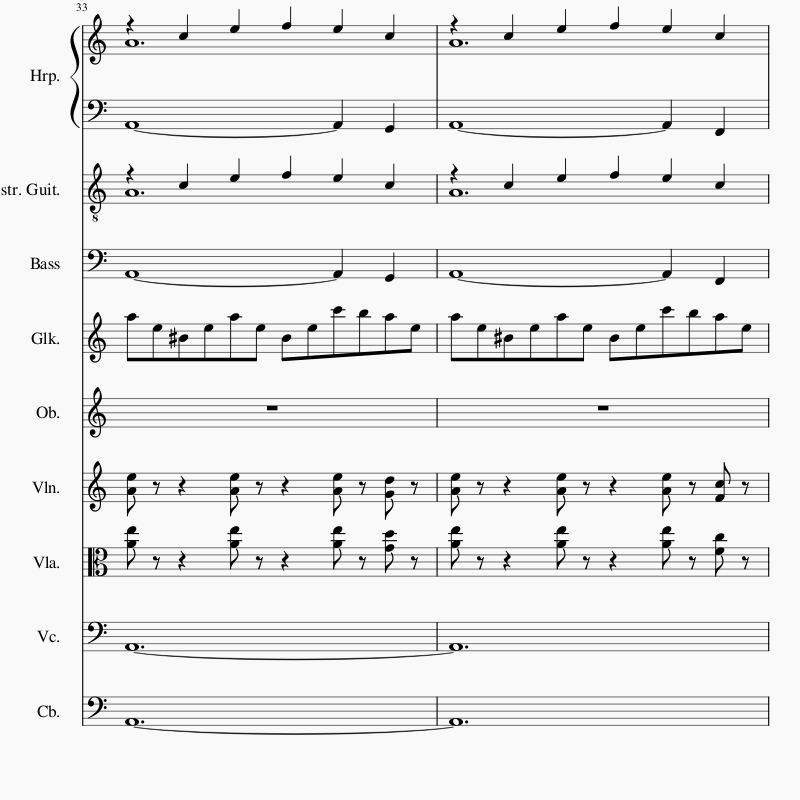

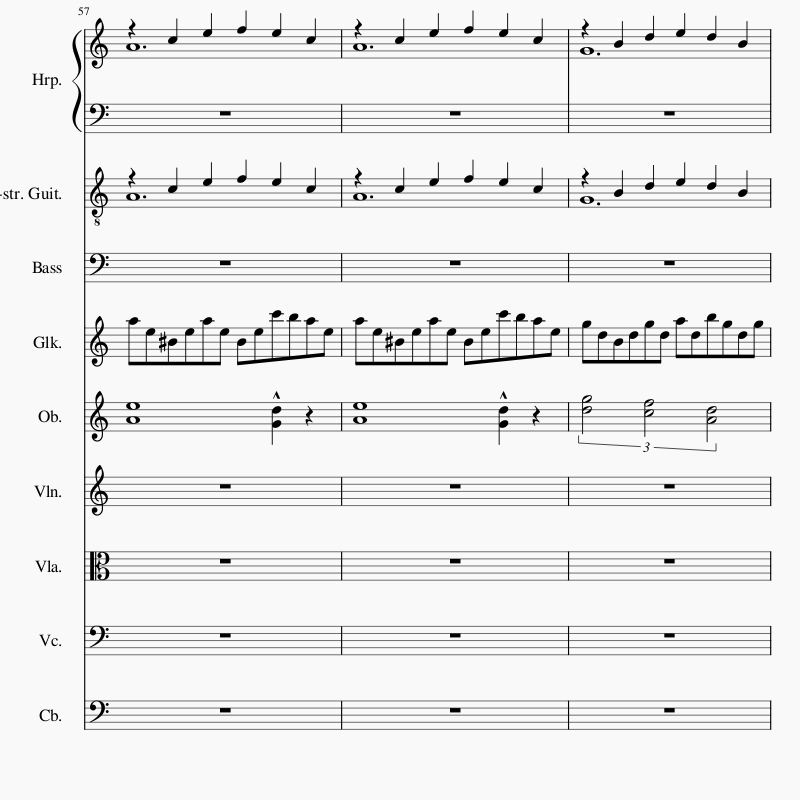

Scene change! I arrange my song as one would a story; with a first, second, and third act. The first acts follows the primary theme I'm creating. As you listen to it, you'll start to imagine what comes next. After the first act has come to a reasonable conclusion, I move to the next act. The second act, for me, comes naturally. If necessary, sometimes, I create a new pattern. There is always a substantial change to the music. While it logically follows the first act, the melody is often dramatically different. In some cases, though, it's not. Occasionally, the second act of one of my songs simply repeats the first act and alters in intensity. Strange New World is an example of this. Once my second act has reached its conclusion, my third act always repeats the them of my first act with a clear change in intensity and instrumentation. Again, in the case of Strange New World, while all three acts are distinctly different, they all follow the exact same melody. Act one is a firm foundation. Act two is an increase in urgency and intensity. Act three's message is a dramatically quiet voice.

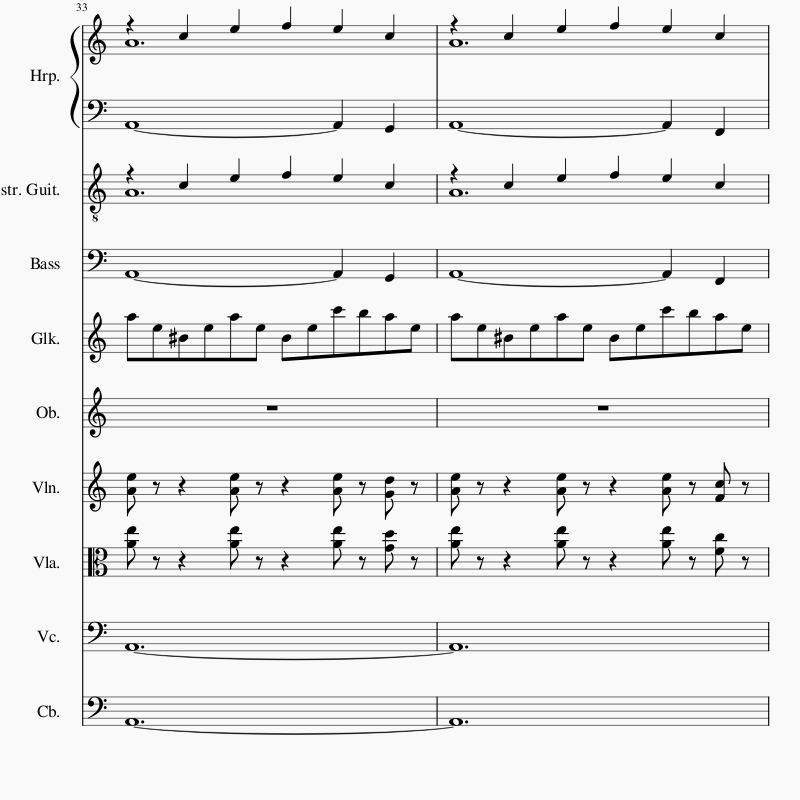

The second act of Strange New World is virtually identical to the first, but it does deviate in a very important way. It's now clear that the first act has been telling us of a matter of importance. It's a matter that bears repeating. There's a specific goal in mind and our questor must focus upon in. However, in the second act, the cello and contrabass have joined the discussion, and their wise voices add authority and credibility to the first act.

The third act abandons the ponderous openings of the first two acts, and goes straight to the narration, but gone are the affirming and authoritative voices of the bass instruments. Now, the third act is a quiet, desperate plea. Remember what you've learned here; everything depends on it.

Striking a Chord

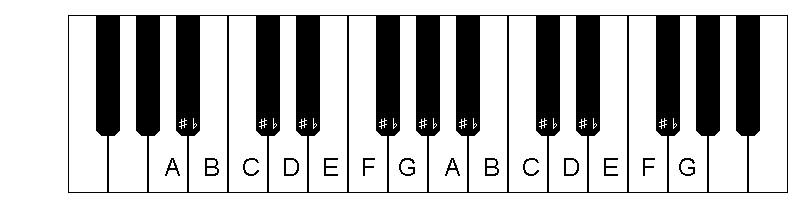

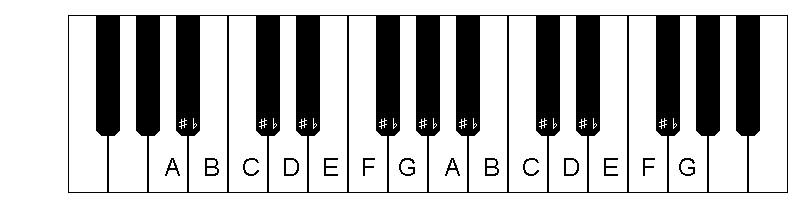

I've been talking about harmony, but how do we do that, you ask? Well, whenever you mix notes, they have to be different enough that they don't sound harsh to the ears. The notes have to be in a certain range. The distance between notes are denoted as “steps”. Look at the keyboard of a piano.

A whole step is always divided by one note. From A to B is a whole step. From F to G is a whole step. But from B to C is only a half step (note that there is no black key between them.). So to get to a whole step, you would have to go from B to C#, or C sharp, or you would have to go from Bb, or B flat, to C. If you sound several notes at once, you create what's called a chord. The distance between notes is going to be your measurement of what that chord will sound like. If you sound A and A#, the chord is going to sound discordant, like a toddler banging on the piano. You'll have similar results if you try to sound A and B simultaneously. It is going to sound harsh in the ear, and the notes are going to be too close together for your hearing to resolve them together. Listen carefully, it will sound as if the notes are alternating. They're not, actually. They are simply too close together for you to hear them at the same time. This is what causes that grating, harsh discordance, and you'll usually want to avoid this (there are times when your music may make use of a discordant note here and there, but it's not extremely common, and the use of discordant notes is generally reserved for music that attempts to create an unsettling atmosphere; horror and suspense writers will want to have a closer look at them.).

Your most common chords will rely on fourths and fifths. To understand what these are, take another look at the keyboard. Sound the notes G and B. This is a fifth. How is this a fifth? Count them!

1. G

2. Ab

3. A

4. Bb

5. B

Five notes total from G to B. Sound GBD to create a major chord. Note that GB equal a fifth while BD equal a fourth. If you switch the placement of the fourth and the fifth, making the fourth first, and the fifth second, GBbD, you create what is called a minor chord, and you can hear the big difference between them. It is the difference between triumph and defeat, joy and sorrow, clarity and madness. When harmonizing between multiple instruments, remembering how chords interact will help. Go back up to the numerous examples from Strange New Worlds. Although there are multiple lines playing different melodies, their harmonics are being reasonably kept in that fourth and fifth range with each other. Mind you, this rule can be easily broken successfully when you've got a melody running and discordant notes will be going by quickly enough that they actually sound good and help the piece, but remember; if you've got a spot that sounds like your violinist sneezed, check to see if everything on that measure is keeping together with that fourth and fifth range.

Sometimes, Less is Less and More is More

So, you've written a piece of music. I don't know what it sounds like. You're probably not too happy with it, but I promise, great things can be done with it given time and experience, but one you notice is that it's lacking oomph. There's no drive. The trumpets sound thin. Well, there is a solution to this. Did you know that the standard orchestra has 60 pieces? That's just standard. Why so many? You probably used eight or nine in a song that sounds like it could be a full orchestral piece. That's because the more instruments playing a specific melody line, the more power it has. If you think your single trumpet playing a fanfare sounds weak, imagine four trumpets playing it. You'll also notice that making them louder doesn't seem to make them stronger. Multiplying the number of instruments DOES. I've struggled with this, too. When one trumpet playing something isn't working, try five trumpets playing it. Or similar sounding instruments. Have a trumpet, cornet, and a treble trombone playing that line, and listen to the difference it makes. Put some flute in your oboe. If your music sounds flat, this is how you make it three dimensional. Fun fact: This is why orchestras have 60 pieces. Because in giving your music depth of sound, more is more.

Conclusions?

I'm not nearly finished. Should I keep going or should I let you digest everything I've said? Eh, I think I've probably given you a lot to chew on. I'm not teacher and I really don't know how to meter information. I'll read comments, if there are any, and I'll see what I need to address. Next time, I'll probably tell you an easy way to remember what notes are where on the staves. Maybe a little more. Probably a little more. Who am I kidding? I have absolutely no self control and will probably ramble just as badly as I did in this article.

This assumes that you are a beginner.

This is not an epic course like Slip Into Ruby. This is fast and dirty, and will be making assumptions about your ability to hear patterns.

There are so many considerations when thinking about what you want your video game to sound like. Is it going to sound like the 8-bit trashterpieces of the golden age of Atari, Intellivision, or Spectrum ZX? Just how retro do you want your music to be? Do you want it to be an orchestral masterpiece that would make Nobuo Uematsu feel inadequate? Well, no matter what style of music you want, you can rest assured that I am going to tell you one, specific way to make music and for anything else, you will be on your own. Why does this not matter? Because whether you're making 8-bit or realistic orchestral sounding music, it entirely depends on the sound of the instruments you're using and how much mixing and processing you want to do after you've written your song.

The Available Tools

Digital Instruments

A variety of digital equipment is available. The most common you'll be familiar with are digital keyboards and pianos, but these tend to cost several thousand dollars. The same is true of digital violins, cellos, guitars, and such. People who go into music stores get told a lot of things. “If you really want to write music, you need the best, and most versatile equipment on the market.” Let's be perfectly honest here; salespeople are absolutely full of shit. Beavis and Butthead know more about getting laid than a salesperson knows about what you need. Rest assured you can do exactly everything and much more than with the Roland Fantom, or the latest Alesis that's going to set you back 20 or 30 thousand dollars that the salesperson is telling you about. Do you know what else can do absolutely everything that that Roland Fantom, Alesis, Korg Trinitron, or Kawaii Z-1000 can do? Your computer and a 200 dollar MIDI controller. And realistically, you don't even need the MIDI controller unless you're using a Digital Audio Workspace, or DAW.

To be fair, many DAWs don't require you to have a MIDI controller, but they're not very easy to figure out without one. DAWs are programs that essentially function as full music studios. Once you've learned how to use one, you can make some amazing music. For these articles, though, forget about DAWs because we're going as basic as possible. DAWs give you versatility as a musician, but they're not necessary, and the only reason I'm telling you this is because I'm trying to give you easy routes to learning how to write music. DAWs require a lot of experience as a musician and I am frankly assuming you're a beginner if you're reading this.

I don't use a DAW for the music I have publicly released and I think my music is pretty alright. I do use a DAW. I use Reaper. But everything I've done on it is experimental and I don't spend a lot of time with it. So, what can you use if you don't need a DAW? Well, there are a number of freewares available that can help you make quality music. Musescore 3 is free notation software that is capable of composing full orchestral scores and it is my preferred program. If you don't feel comfortable with notation, then your other option is software that uses piano roll writing. The most popular freeware for that is LMMS.

Soundfonts and Virtual Studio Technology

So, let's start with Virtual Studio Technology, or VSTs. A VST is a plugin. It contains a set of instruments, such as different styles of guitars or different pianos. Upon uploading to software, it adds a widget that gives you the VST's own control panel that controls its soundfont. I don't know if LMMS uses them, but this is the only time I will be mentioning VSTs since the program I work in doesn't use them. You've likely noted that VSTs contain a soundfont. Musescore 3 only requires soundfonts directly uploaded to its sound file. Try out both Musescore and LMMS, or any other studio you have and see which one you prefer.

Soundfonts, as the name implies, are the sounds themselves. VSTs have soundfonts installed in them, but you don't really need VSTs with the more basic notation software. Soundfonts are libraries of sounds. Some of them have full orchestras. Musescore comes with a soundfont that contains a full orchestra, a full synthesizer set, and dozens of ethnic instruments whose names you can't pronounce. Other soundfont libraries are available online. You can use them by downloading, unzipping, and dropping the file directly in Musescore's sound folder. Once it's in, you'll be able to access the new soundfont in Musescore's synthesizer selection in its View menu. Simply tick the synthesizer box and it will open a window that shows you the available soundfonts. Move the one you want to use to the top of the list. On every boot of Musescore, you'll need to do this since the system always starts with the default on top. If you want the new soundfont to be the default, simply move it to the top of the list and press the “default” button.

Now what do you do?

Play with it. Forget learning how to write music for a while and play with the sounds you can make with this software. You probably have about 200 instruments at your disposal right now. Add channels or staffs and make as many varied noises as you can. Go wild. Get silly. Let me help you identify some stuff to help you maximize your tomfoolery:

Want faster notes? Add more flags! In theory, you could add as many flags to a note as you like to keep making it faster. Practically? You're eventually going to run out of room on the sheet and if you're writing your score in 524,288/524,288, you're just going to give the listener tinnitus. And maybe a seizure (No, seriously. Google “black MIDI”. Just like flashing lights on a monitor, chaotic noise beyond a certain frequency and speed is dangerous. The military has actual weapons based on this.).

These aren't the only notes available, but they are the base note types. You can alter their speed by placing them in tuplets (tuplets divide a beat by a specified amount, a beat being the length of a quarter note in the standard 4/4 timing.)

You can also alter a note's speed by adding an augmentation dot. This changes the notes speed to halfway between the dotted note and the next sized note. In the following example, the half note is turned into a three quarters note with an augmentation dot.

There are other ways to lengthen a note, such as with ties. The following example is quite literally the same note as above, simply expressed with a tie instead of an augmentation dot.

So, what are beats? Well, do you see that 4/4 at the beginning of the staff? That measures how many notes of a certain type can fit in a measure. In the expressed measure, a single whole note can fit, and nothing else. It is the long note. A half note, when expressed, lasts for half as long as a whole note (shocking, right?). A quarter note lasts for a quarter as long as whole note or half as long as a half note, and is what the 4/4 timing specifically denotes. 4 quarter notes can fit in a 4/4 measure. No more, no less. Now, you can see how music can be timed and measured. These are the beats, and in a lot of music, there's nothing audio expressing the beat, but in most music, you've usually got a drum, or a set of drums keeping time. But even when there's nothing expressing the beat, you can still hear it. If the rhythm is off on even one measure, it stands out to our ears painfully.

You can change the volume of an instrument with the dynamic selection in the left “palettes” menu. The dynamic ranges are as follows:

ppp = pianississimo (softest)

pp = pianissimo (softer)

p = piano (soft)

mp = mezzo piano (soft mid-range)

mf = mezzo forte (hard mid-range)

f = forte (hard/loud)

ff = fortissimo (harder/louder)

fff = fortississimo (hardest/loudest)

There are other dynamic ranges that I'm going to ask you not worry about. They have subtleties that as a beginner, you're not going to really be able to hear, and we're going to be able to address those subtleties anyway with another method. We are, after all, dealing with MIDI, and there are certain things that MIDI cannot do, but that's where processing will come in.

But enough serious talk. Armed with the basic knowledge I've just given you, you can be somewhat dangerous with this software. Revel in your toy. Spend hours with it. Spend days with it. Try to duplicate your favorite songs. Do a MIDI rendition of Bad Romance. Make brilliant chaos! Children make it obvious that humans learn through play, but we seem to think that play is useless once children have learned how to read and tell time. This is totally false. The best way to learn a system is by playing with it. Push all the buttons. Try out all the instruments. Make all the sounds. Make gibberish! It'll be great!

I have come from the future of this article to isolate this spot, because I feel like more than anything else I say anything in this article, following the advice in the above paragraph is the most crucial thing you can do. Play with the music. By all means, waste type making gibberish songs you think sound cool. Try and replicate your favorite pieces of music. Do the Terminator theme. Try to recreate your favorite Final Fantasy songs. Legend of Zelda. Super Mario Bros. Arrange your favorite cartoon themes. Try to do some Daft Punk. Obsess over this. This more than anything is going to help you understand how music comes together.

Want to make multiple different instruments make noise at the same time? You'll need more lines for that. Add instruments in Musescore by going to the edit menu and finding “Instruments”, or press “I” on your keyboard. You'll get a window with a list of instruments that you can add or remove.

Once you're done playing around, we can start discussing methods of music creation. We're going to begin with a bit of basic conceptualization. This is not music theory. I never studied it. This is simply an explanation of my thought processes. If any of it coincides with actual music theory, I will consider it a happy coincidence.

Pattern Seeking isn't a Bad Thing

At the most basic level when I write music, one of the things I will do is start by creating a pattern. This is the most common way I approach a new composition. I will make numerous musical patterns before finding one that really sticks with me. That could be a melody line, a bass line or a drum line. Let me immediately clarify here that this method is best described as banging on the keyboard like an idiot and seeing if I hear something like, and then taking that, isolating it, and trying to make it make musical sense. A few guidelines to employ:

Make a pattern that fits in a single measure. This doesn't have to be the 4/4 scale. If you've come up with a pattern that doesn't fit in the 4/4 time signature, don't just throw it out. See if it fits in another time signature. Caveat: the potential time signatures are infinite, but once you start to leave the common ones, it starts to get tricky. If your beat does not fit in any regular time signature, you might find yourself in irregular time signatures. If this happens, you'll have a difficult time getting the timing right. There are ways of dealing with this, but at this point, I recommend altering your musical pattern to something that fits neatly into one of the commonly used time signatures, because irregular beats can be a real headache. If ALL instrument lines you make follow that irregular beat cleanly, then it works. Go with it. If not, you're in for a rough time.

For Shell Game, I came up with a simple guitar riff and assigned a Ukulele to it. This riff dominates the entire song.

Repeat the pattern. This is video game music. With a few exceptions, it needs to loop cleanly, and repetition is going to be your best tool for making your whole song able to repeat itself.

All things in modulation. Repeat the pattern, but don't let it drone on. Modulate the key (this is when the music's notes go higher and lower). Change the notes the in the pattern at some points. Alter the pattern and have it alternate with the original pattern.

For Strange New World, my chosen pattern was a repeating arpeggio on the harp. As you can see, once I've repeated the pattern, I transpose, or modulate, down a step. You can also see that eventually, I change the note order and replace two quarters with a half note. Think of this line as a sentence. The first measure is a statement. The second measure confirms the statement. The third measure asks a question about the statement. The fourth measure offers a counterpoint to the statement. This isn't a discussion, yet. So far, we only hear one speaker. But in that fifth measure, you can see the sentence is being repeated, and a second speaker, the bass line of the harp, is chiming in with its own opinion. Basically, you see the main speaker make a point, confirm it, wonder if it's true, suggest an alternative, and then engage in conversation about that point with another speaker.

It's almost like it writes itself! I don't know how it works for other people. I can't help but think that maybe I think really strange, but when I listen to my pattern, I can sort of start to hear other instruments accompanying it, and I quickly get a very firm grasp of what my song sounds like. At this point, I write it down. I worry that maybe you're different. Whatever the case, I add instruments and I add accompaniment as I can hear it gradually come together in my imagination. This is going to get into a lengthy discussion about structure that I'm going to save for later (basically, what instruments should accompany the first one, are you even going to use the first one or change it to something else, what instruments naturally go together, don't go together, etc. etc.). Your accompaniment needs to harmonize in some way with.

Here, you can see that in Strange New World, I reinforce my treble harp by copying it to a 12-string guitar and my bass harp with an acoustic bass. This adds a personality to the specific sound that one instrument alone wouldn't give.

The glockenspiel is not providing a melody but is adding accompanying harmony to the harp and guitars. We now have five speakers conversing harmoniously.

Violins and violas are now keeping time in a similar fashion to drums. In this instance, I've created a string line that adds importance and gravitas to the harmony. They are dramatically signaling that weighty matters are being discussed and that this conversation is not to be taken lightly. These strings have a staccato sound to them (even though they're not staccato) and are keeping track of the beat just as drums would. Note that I don't bring these instruments in all at once. I start the song with the harp and the guitars. They express the four measure subject once, add a bass line to the subject, repeating it again. The third time, we add a glockenspiel. The fourth time, we add strings. We are now 16 measures into the song. We've stated our point four times.

And now, at the 17th measure the oboe finally joins us. This isn't a harmonizing line. No. You can see that the oboe is saying something very different, so it's going to stand out among the rest of the speakers. This is our melody line and the oboe is the narrator of the tale this song is trying to tell.

Scene change! I arrange my song as one would a story; with a first, second, and third act. The first acts follows the primary theme I'm creating. As you listen to it, you'll start to imagine what comes next. After the first act has come to a reasonable conclusion, I move to the next act. The second act, for me, comes naturally. If necessary, sometimes, I create a new pattern. There is always a substantial change to the music. While it logically follows the first act, the melody is often dramatically different. In some cases, though, it's not. Occasionally, the second act of one of my songs simply repeats the first act and alters in intensity. Strange New World is an example of this. Once my second act has reached its conclusion, my third act always repeats the them of my first act with a clear change in intensity and instrumentation. Again, in the case of Strange New World, while all three acts are distinctly different, they all follow the exact same melody. Act one is a firm foundation. Act two is an increase in urgency and intensity. Act three's message is a dramatically quiet voice.

The second act of Strange New World is virtually identical to the first, but it does deviate in a very important way. It's now clear that the first act has been telling us of a matter of importance. It's a matter that bears repeating. There's a specific goal in mind and our questor must focus upon in. However, in the second act, the cello and contrabass have joined the discussion, and their wise voices add authority and credibility to the first act.

The third act abandons the ponderous openings of the first two acts, and goes straight to the narration, but gone are the affirming and authoritative voices of the bass instruments. Now, the third act is a quiet, desperate plea. Remember what you've learned here; everything depends on it.

Striking a Chord

I've been talking about harmony, but how do we do that, you ask? Well, whenever you mix notes, they have to be different enough that they don't sound harsh to the ears. The notes have to be in a certain range. The distance between notes are denoted as “steps”. Look at the keyboard of a piano.

A whole step is always divided by one note. From A to B is a whole step. From F to G is a whole step. But from B to C is only a half step (note that there is no black key between them.). So to get to a whole step, you would have to go from B to C#, or C sharp, or you would have to go from Bb, or B flat, to C. If you sound several notes at once, you create what's called a chord. The distance between notes is going to be your measurement of what that chord will sound like. If you sound A and A#, the chord is going to sound discordant, like a toddler banging on the piano. You'll have similar results if you try to sound A and B simultaneously. It is going to sound harsh in the ear, and the notes are going to be too close together for your hearing to resolve them together. Listen carefully, it will sound as if the notes are alternating. They're not, actually. They are simply too close together for you to hear them at the same time. This is what causes that grating, harsh discordance, and you'll usually want to avoid this (there are times when your music may make use of a discordant note here and there, but it's not extremely common, and the use of discordant notes is generally reserved for music that attempts to create an unsettling atmosphere; horror and suspense writers will want to have a closer look at them.).

Your most common chords will rely on fourths and fifths. To understand what these are, take another look at the keyboard. Sound the notes G and B. This is a fifth. How is this a fifth? Count them!

1. G

2. Ab

3. A

4. Bb

5. B

Five notes total from G to B. Sound GBD to create a major chord. Note that GB equal a fifth while BD equal a fourth. If you switch the placement of the fourth and the fifth, making the fourth first, and the fifth second, GBbD, you create what is called a minor chord, and you can hear the big difference between them. It is the difference between triumph and defeat, joy and sorrow, clarity and madness. When harmonizing between multiple instruments, remembering how chords interact will help. Go back up to the numerous examples from Strange New Worlds. Although there are multiple lines playing different melodies, their harmonics are being reasonably kept in that fourth and fifth range with each other. Mind you, this rule can be easily broken successfully when you've got a melody running and discordant notes will be going by quickly enough that they actually sound good and help the piece, but remember; if you've got a spot that sounds like your violinist sneezed, check to see if everything on that measure is keeping together with that fourth and fifth range.

Sometimes, Less is Less and More is More

So, you've written a piece of music. I don't know what it sounds like. You're probably not too happy with it, but I promise, great things can be done with it given time and experience, but one you notice is that it's lacking oomph. There's no drive. The trumpets sound thin. Well, there is a solution to this. Did you know that the standard orchestra has 60 pieces? That's just standard. Why so many? You probably used eight or nine in a song that sounds like it could be a full orchestral piece. That's because the more instruments playing a specific melody line, the more power it has. If you think your single trumpet playing a fanfare sounds weak, imagine four trumpets playing it. You'll also notice that making them louder doesn't seem to make them stronger. Multiplying the number of instruments DOES. I've struggled with this, too. When one trumpet playing something isn't working, try five trumpets playing it. Or similar sounding instruments. Have a trumpet, cornet, and a treble trombone playing that line, and listen to the difference it makes. Put some flute in your oboe. If your music sounds flat, this is how you make it three dimensional. Fun fact: This is why orchestras have 60 pieces. Because in giving your music depth of sound, more is more.

Conclusions?

I'm not nearly finished. Should I keep going or should I let you digest everything I've said? Eh, I think I've probably given you a lot to chew on. I'm not teacher and I really don't know how to meter information. I'll read comments, if there are any, and I'll see what I need to address. Next time, I'll probably tell you an easy way to remember what notes are where on the staves. Maybe a little more. Probably a little more. Who am I kidding? I have absolutely no self control and will probably ramble just as badly as I did in this article.

Posts

Pages:

1

I don't know about beginners, but as someone who's been composing for years yet never managed to learn music notation, this guide is very easy to understand. I'll refer to it in the future.

Would it be possible to add a music file to every step of the Strange New World tutorial? To hear the piece being built progressively might help our understanding further.

That is absolutely true and wise advice.

Indeed. I'm going off on a tangent here, but I don't know if that comes from experience, from how strong you feel about your music, how connected you are with it, or some other obscure reasons. Once the skeleton of a music track is set in place, it often seems like the accompanying melodies and chords just pop out of nowhere and fit like puzzle pieces.

Maybe it's similar to when we internalize popular patterns and chords, and then correctly guess the next notes of a song we listen to for the first time.

Would it be possible to add a music file to every step of the Strange New World tutorial? To hear the piece being built progressively might help our understanding further.

I have come from the future of this article to isolate this spot, because I feel like more than anything else I say anything in this article, following the advice in the above paragraph is the most crucial thing you can do. Play with the music. By all means, waste type making gibberish songs you think sound cool. Try and replicate your favorite pieces of music. Do the Terminator theme. Try to recreate your favorite Final Fantasy songs. Legend of Zelda. Super Mario Bros. Arrange your favorite cartoon themes. Try to do some Daft Punk. Obsess over this. This more than anything is going to help you understand how music comes together.

That is absolutely true and wise advice.

It's almost like it writes itself! I don't know how it works for other people. I can't help but think that maybe I think really strange, but when I listen to my pattern, I can sort of start to hear other instruments accompanying it, and I quickly get a very firm grasp of what my song sounds like.

Indeed. I'm going off on a tangent here, but I don't know if that comes from experience, from how strong you feel about your music, how connected you are with it, or some other obscure reasons. Once the skeleton of a music track is set in place, it often seems like the accompanying melodies and chords just pop out of nowhere and fit like puzzle pieces.

Maybe it's similar to when we internalize popular patterns and chords, and then correctly guess the next notes of a song we listen to for the first time.

Avee

I don't know about beginners, but as someone who's been composing for years yet never managed to learn music notation, this guide is very easy to understand. I'll refer to it in the future.

Thank you! If nothing else, I'm glad I'm not the only one who understands what I was trying to say.

Would it be possible to add a music file to every step of the Strange New World tutorial? To hear the piece being built progressively might help our understanding further.

You know, why didn't I think of this? Done.

Pages:

1